A Social & Environmental Equity Investing Framework for Better Real-World Outcomes

Investing can often feel like steering a ship through stormy seas, traversing risks seen and unseen. In recent years, the siren song of investment products that appear aligned with achieving genuine social and financial returns—but are merely designed to attract assets—is one such danger. And this trend, coupled with economic uncertainty, creates a perfect storm of confusion around how best to build resilient, impact-forward portfolios.

Whether we crash into a recession remains to be seen, but if history is prologue, market downturns would disproportionately harm communities already struggling to stay afloat. Now is not the time to turn back. Adopting a more disciplined approach to investing for social and environmental equity (SEE) can help investors minimize portfolio risk and maximize impact, even during flagging markets. In this paper, we review the momentum experienced in sustainable and impact investing (SII) and the historical relationship between global recessions and inequality. We then explain the rationale for staying the course during turbulent times, and introduce a framework designed to help investors produce better financial and impact outcomes in any market cycle.

Part I: Risk-Off Sentiment Threatens Momentum in Social & Environmental Equity

According to our 2022 biannual client survey, 65% of institutions had actively engaged in SII and environmental, social, and governance practices, a 29-percentage point increase relative to the 2018 response. The primary drivers of increased uptake are better education around the opportunities and risks of sustainable investing, increased clarity around clients’ mission priorities (and ways to express those views in portfolios), as well as growth of strong performing and aligned investment options. Additionally, social and/or environmental equity were among the top priorities for sustainable and impact investors surveyed, with one-third of respondents making impact investments across three or more impact themes. These results draw in sentiment from 2020, which shined a spotlight on widespread social and economic disparities impacting marginalized communities and compelled investors to focus more on the interconnectedness of social and environmental themes.

Despite this evolution and recent momentum, there’s still risk of investors pausing or even reversing course on investing for SEE amid a critical time for marginalized communities. During heightened market volatility and falling market returns, availability and recency biases tend to lead to decreased risk tolerance and a race to implied safety. Some investors might consider investing in sustainable and/or impact themes to be too risky. Worse yet, sustainable investing initiatives can be labeled as “idealistic” or “ancillary” despite the materiality of SII factors.

Economic downturns accelerate the pace of economic and social inequality, according to a recent study conducted by the Bank of International Standards (BIS), 1 which found that, on average, income inequality grew twice as fast during recessions. Contractionary periods exacerbate a wide variety of social indicators—from job insecurity and health outcomes to generational wealth distribution—while stoking uneasiness among the very investors that want to effect positive change at the same time. This perfect storm of macroeconomic factors and investor sentiment threatens progress made on SEE over the past several years. Still, turbulent markets are not the time to steer away, but to forge ahead.

Part II: A More Disciplined, Intersectional Approach Can Help Minimize Risk and Maximize Positive Impact

A Framework for Stable and Volatile Times

In Social Equity Investing: Righting Institutional Wrongs (2018), we define social equity investing as “investments to promote equal opportunity and access for all, regardless of background.” The SEE framework is a natural evolution of our investment approach, overlaying the following three-step process:

- Rigorously assessing each investment manager’s alignment with SEE themes and categorizing them on a spectrum of SEE alignment; 2

- Mapping managers based on their investment strategies against a five-stage thematic pyramid; and

- Executing an engagement program designed to improve alignment of managers that are weakly aligned with SEE and explore new opportunities.

This approach addresses myriad pain points we have uncovered. These include the association of social equity investing with lower or concessionary returns, a failure to acknowledge the intersectionality 3 and interconnectedness of sustainability and impact issues that result in siloed portfolio approaches, and inaccurate language used to describe and define social equity—particularly the conflation of broad social and racial equity with diverse manager investing.

The SEE framework’s five-stage pyramid (Figure 1) is inspired by a well-established theory in psychology, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and offers a more disciplined, clearer, human-centered approach to investing for SEE.

Investable social and environmental themes—which we view as core to creating an equitable society—are mapped to a hierarchy of needs, rather than a primarily demographic or social lens (e.g., race and gender). The hierarchy provides a visual representation of the relative weight or impact of investing in a particular theme. For example, the base of the pyramid addresses physiological or basic existential needs of all people, regardless of race, gender, or geographic region. We all need clean water, air, food, safety, infrastructure, and affordable and reliable means of getting around to survive. It is important to note that while civil rights and justice themes are also represented at the base of the pyramid—a reflection of their fundamental importance—they are not easily actionable through market rate investable instruments. Instead, we currently see grants and program-related investments (PRIs) as the primary capital source for these themes.

Progressing up the pyramid, we approach more “psychological” or “esteem” needs, which are defined as those that foster greater feelings of acceptance, status, and independence, and go beyond the very basics of subsistence. The apex of the pyramid represents “self-fulfillment” needs that refer to the realization of a person’s highest potential and ability to seek personal growth. Its relative size on the pyramid reflects the limited, albeit growing, grant or PRI opportunities we currently see in arts and culture. Lastly, as illustrated by the arrow ascending the right flank of the pyramid, the framework fully integrates racial and gender equity into every theme and reinforces them—and myriad other forms of equity—at every step. Therefore, racial and gender themes do not lose, but instead, gain prominence in SEE investing.

All told, the approach leaves investors with a clearer way to express their values in portfolios and to visualize alignment of investment managers with portfolio goals and objectives without prescribing the order in which to invest.

Maximize Impact and Enhance Returns With a Systems Lens, Improved Investment Processes and Manager Selection

The framework is designed to help accelerate investment in SEE themes in three important ways:

First, it acknowledges the role of systems in exacerbating inequities and therefore leans into a systems approach 4 to support investors in reversing those inequities. It does so by purposefully building in the interconnectedness of myriad sustainability and impact issues and, critically, weaving in environmental equity and climate change as core tenets in our discussion of social equity. A more holistic portfolio approach benefits a wider group of global stakeholders and, if done well, will help to enhance long-term climate, social, and financial resilience of portfolios.

Second, in keeping with our approach to debias the investment decision-making process, the framework explicitly seeks to reframe SEE themes in terms of the universality of human needs. Mapping themes in this way, rather than social constructs (e.g., race or gender), works to reduce the cognitive barriers that trigger implicit biases, restrict fruitful discussion about the intersectionality of themes, and ultimately limit investment uptake. For example, too keen a focus on a specific “gender lens” or “racial lens” can potentially compromise investment processes. This could result in unnecessarily siloed portfolios, which threaten the overall scalability of global impact.

Finally, strong manager selection and diversification are hallmarks of this intersectional approach. Improving the classification of managers that have closer alignment with SEE and enhancing engagement practices with those that are not quite there are pivotal to better outcomes. Sample engagement questions might include:

- How does the firm consider equity and inclusion in the evaluation of prospective investment opportunities and pipeline generation?

- How specifically does your strategy incorporate and promote equitable access for women and marginalized communities within each portfolio company’s long-term strategic plan and operations?

These are challenging questions, but all responses from all managers across all strategies, regardless of an explicit SII focus, are data points that enhance our ability to better classify managers that meet our clients’ needs. The framework defines an SEE investment manager as one that intentionally targets social or environmental equity themes at the strategy level (e.g., supporting diverse entrepreneurs, thus targeting the financial inclusion theme) or through the products and services offered by their portfolio companies.

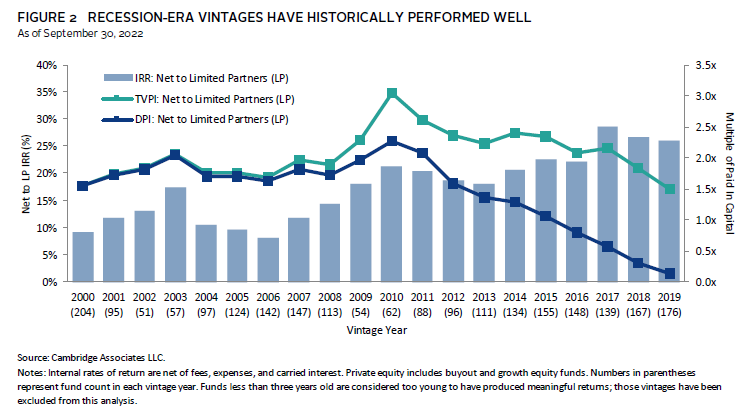

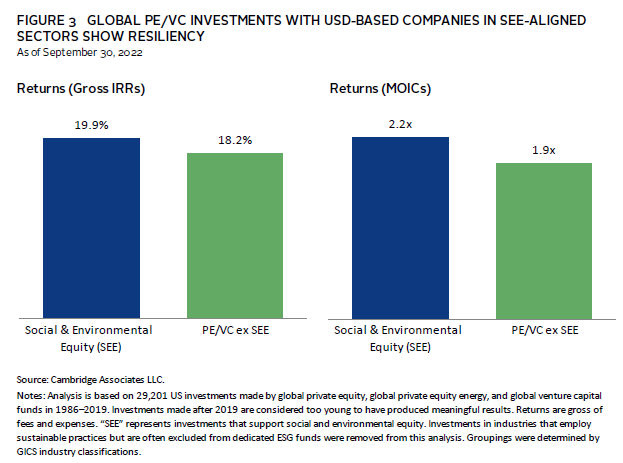

Leaning into SEE thematic investing may help buffer portfolio performance and mitigate risk, particularly in market downturns, as we believe many industries that align with high-impact SEE themes tend to be less prone to the negative effects of recession. In fact, while recession-era vintages have historically performed well (Figure 2), a deeper look at SEE-aligned sectors exposes resilience (Figure 3). We recognize that many SEE themes overlap with historically defensive sectors, but these are also areas that address fundamental human needs and are ripe for innovation. Managers with high SEE integration are intentionally focused on making better and more accessible products within these industries to address those needs.

Applying the Framework: A Foundation’s Impact Portfolio

A hypothetical scenario brings this approach to life and illustrates how the SEE framework can help improve the ability to select the most aligned managers for long-term portfolio sustainability. This case study consists of only private investments managers, given their unique ability to effect impact more directly through control and influence of underlying portfolio companies.

Applying the three-step SEE approach, each manager in the impact portfolio is initially analyzed to gauge the level of authenticity, intentionality, and materiality of focus on SEE themes. This assessment begins with a rigorous due diligence and manager landscaping process. Next, managers are classified in an easy-to-use stoplight format (red illustrating no material SEE integration and green representing the highest SEE integration) before being mapped to the thematic area in the SEE pyramid that best aligns with their primary investment strategy (Figure 4). The final step is to develop an engagement strategy in partnership with the investor. While all managers are eligible for engagement, those with less than a green classification present the greatest opportunity for engagement around these issues.

The analysis reveals an impact portfolio that is less aligned than intended with their stated racial justice/equity mission. For example, there is a dearth of managers with strong SEE integration (green), presenting an opportunity for further engagement and discussion among investment committee members around their managers’ intentions and true fit in a social equity mandate. Additionally, a concentration in sustainable real assets and climate tech venture capital managers that have minimal SEE integration (orange) is exposed. Finally, the portfolio has strong diverse manager representation, which suggests a keen focus on diversifying managers, but also a potential confluence of diverse manager investing with SEE investing (e.g., red sphere, a diverse manager with no material SEE integration). Overall, this process creates an opportunity to dig deeper into what the investor owns and to find ways to improve the portfolio’s mission alignment through improved engagement and future manager selection.

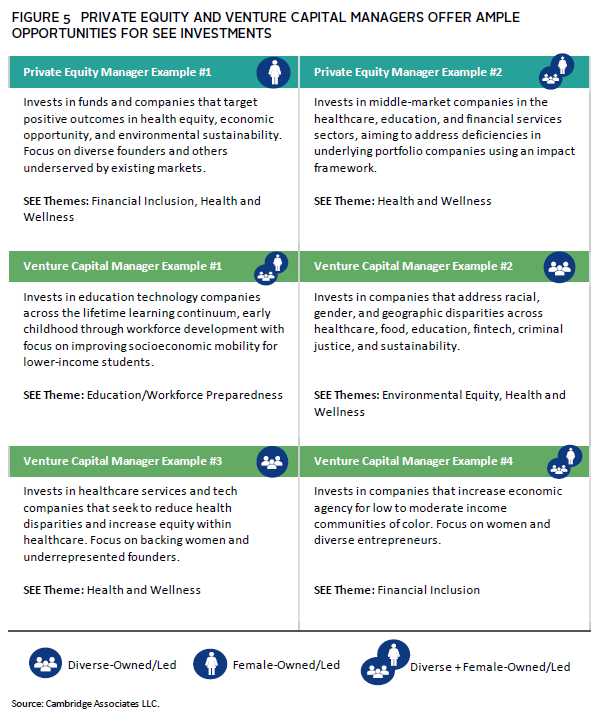

There is no “one size fits all” approach to building a resilient and impact-forward portfolio. However, leveraging the SEE framework can support discipline, rigor, and more thoughtful implementation strategies across market cycles. We believe there is an existing and growing universe of SEE-aligned managers that have the potential to outperform broad equity benchmarks and to reduce risk because of their integrated focus on improving social and environmental equity (Figure 5).

Conclusion

The SEE framework is designed to induce investment in SEE themes through an intersectional human-centered approach. While we introduce it in the context of economic downturns, it is a useful tool that is applicable in all market cycles and can help investors to reduce bias in the investment process, enhance portfolio construction and unearth new sources of alpha, and mitigate portfolio risk. Risk-averse behavior is characteristically human. Whether in calm or stormy waters, we should batten down the hatches and sail with resolve toward sustainable solutions that address and advance the fundamental needs of all human beings.

Drew Carneal and Caryn Slotsky also contributed to this publication.

Footnotes

- Luiz Awazu Pereira da Silva et al., “Inequality Hysteresis and the Effectiveness of Macroeconomic Stabilisation Policies,” Bank for International Settlements (BIS), May 2022.

- A manager with high SEE integration is one that intentionally targets one or more investable social or environmental equity areas: health/wellness, environmental equity/climate justice, education/workforce preparedness, affordability/physical security, and transportation/sustainable infrastructure.

- Intersectionality describes the interconnected and overlapping systems of discrimination across social categorizations. The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in 1989. An intersectional approach to investing, similarly, acknowledges that certain risks and opportunities are interconnected and cannot be separated. Investors that pursue an intersectional approach within their portfolios may enhance the long-term climate, social, and financial resilience of their portfolios, benefiting stakeholders.

- Systems thinking/lens or approach in the context of this discussion acknowledges the linkages of material sustainability and impact factors to one another and to portfolios. It is a way to make sense of complex systems by exploring the interrelatedness of the parts, boundaries, and perspectives within that system. It recognizes that complex systems cannot be fully understood from only one perspective, and complex problems cannot be solved by any single actor.