Social Equity Investing: Righting Institutional Wrongs

Many institutional investors have long sought to promote social equity through grant making and other philanthropic endeavors. With the field of impact investing maturing, these institutions are now increasingly seeking investment solutions to accomplish the same goal. Yet this effort raises important questions: What is social equity investing? What does it look like in practice? And how do social equity investments fit in a portfolio?

In this paper we review the current state of social equity in the United States, highlight eight core social equity issue areas, and discuss the lessons we’ve learned in constructing portfolios with these investments. We define social equity investing as investments to promote equal opportunity and access for all, regardless of background, but we understand that many investors have different definitions. 1 While investors need to be mindful of risks, we believe that investments can be made to promote a social equity impact agenda across the portfolio.

The State of Social Equity in the United States

For more information on impact investing, please see the following Cambridge Associates’ publication: Navigating the “Alphabet Soup” of Mission-Related Investing.

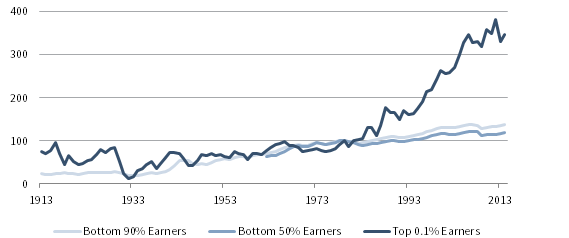

The United States continues to experience high levels of inequality in income, access, and opportunity. The Economic Policy Institute found that real wages for most US workers have seen minimal change since the 1970s, while wages for the top 0.1% have nearly quintupled (Figure 1). Also, data from The Brookings Institution indicate that the chances of economic mobility are decreasing, with one study finding that, while nine out of 10 children born in 1940 had higher earnings at age 30 than their parents at the same age, for those born in 1980, the number dropped to one in two.

FIGURE 1 REAL WAGE GROWTH FOR US WORKERS

1913–2014

Source: Economic Policy Institute.

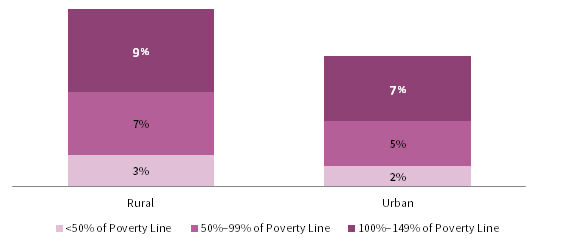

People living in the United States also face disparities in access to education, health care, and even civil rights. Data suggest that income profiles are correlated with many of these access inequities, with lower income populations having less access. Other demographic information, such as zip code, gender, race, and sexual orientation, correlates with inequality as well. For example, a study by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention found that people living in rural America are more likely to die from preventable diseases compared to their urban counterparts. They also face higher levels of poverty compared to their urban counterparts (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 PERCENT OF US WORKERS IN POVERTY

2016

Source: US Census Bureau, 2016 Current Population Survey.

Note: Figure includes US householders aged 25–54 that worked at least part of the year in 2015 and by poverty threshold.

LANGUAGE MATTERS

As we engaged with practitioners and other experts, we heard different perspectives on how they defined social equity investing. Some highlight education, others healthcare, and still others, the environment. We also heard strong preferences for the best terminology to employ, particularly when it came to “social justice” versus “social equity.”

These differences point to the need for greater precision when we talk about social equity. As the Grantmakers for Southern Progress put it, “a singular way of talking about the work will not resonate with the diversity of audiences” engaged in it! However, the potential for different perspectives should be recognized and investors should seek to ensure they are effectively communicating their social equity aims.

Economists argue these issues create economic risks for our society. A 2017 article from the World Economic Forum noted that inequality may threaten “the very foundation of economic growth,” particularly if that growth is not inclusive. At the same time, there is real economic opportunity to be gained from creating more inclusive economies. The Center for American Progress estimates that if the racial education achievement gap were closed, the US economy would be nearly $2.3 trillion larger in 2050.

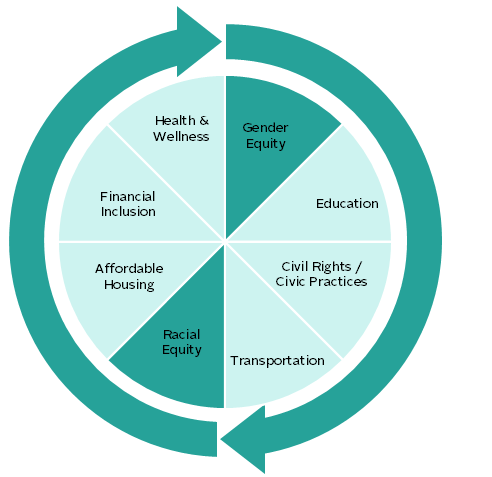

Understanding Social Equity Issue Areas

We highlight eight social equity issue areas in Figure 3 that we view as core to creating a socially equitable society: gender equity, education, civil rights/civic practices, transportation, racial equity, affordable housing, financial inclusion, and health & wellness. 2 Most social equity issue areas are investable, but a few currently do not lend themselves to traditional portfolio structures at this time and are likely best accessed through public policy or philanthropic efforts.

FIGURE 3 EIGHT CORE SOCIAL EQUITY ISSUE AREAS

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Although we present the issue areas as distinct, investors should keep in mind that in practice, the themes are interrelated. Research on the social determinants of health shows that access and quality of health care is often entangled with education, the environment, and economic stability. Therefore, investors seeking to improve health issues must recognize that other factors will influence outcomes.

To highlight another example, in education, children’s academic success depends on their classroom experience as well as on reliable transportation, stable housing, and access to nutritious food. Consequently, communities often require a robust set of solutions aimed at tackling the myriad pain points, rather than a silver bullet. Practitioners are advised to understand the broader landscape of issues that lay before them, and the need to take these multiple issue areas into account to create comprehensive, sustainable, and truly transformative solutions.

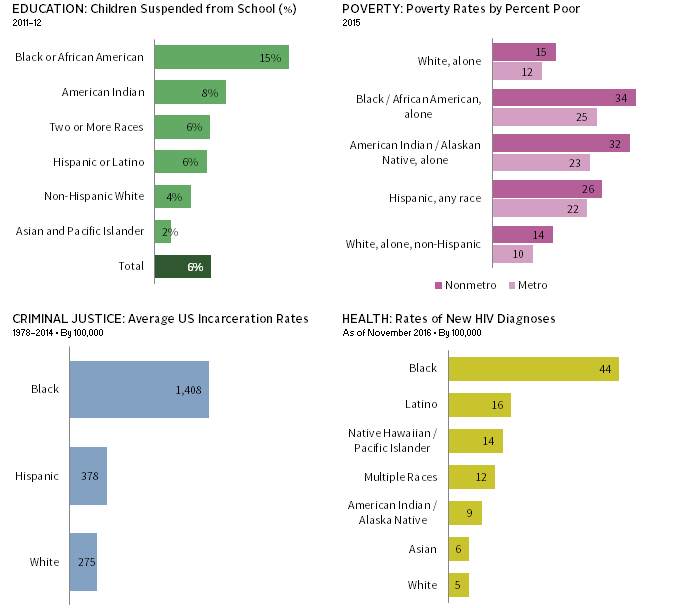

This dynamic is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in advancing racial equity. The legacies of racism and racial barriers are deep and complex, and data indicate that inequities across almost nearly any topic—education, health care, financial inclusion —tend to be more pronounced for people of color (Figure 4). In effect, investing to advance racial equity demands particular attention and understanding of the interconnectedness of the underlying themes within social equity.

FIGURE 4 RACIAL INEQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Kids Count Data Center; US Census Bureau; and United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics, 1978–2014.

Successful capital deployment to support communities of color also requires an understanding of the economic viability of those markets. Fortunately, institutions are seeking to better understand these dynamics. The Selig Center for Economic Growth found that racial minority groups represent the fastest gains of buying power within the United States. It estimated that the combined buying power of blacks, Asians, and Native Americans in 2016 was $2.2 trillion, a 138% gain since 2000. The study also estimated that the buying power of Hispanics increased by 181% to $1.4 trillion. In contrast, the buying power of white consumers only increased by 79% during this same period.

In addition to the economic upside of investments within communities of color, research has also uncovered that there are real costs to bear by not addressing racial inequities. In 2018, the WK Kellogg Foundation argued that raising the average incomes of people of color to the average incomes of white people would generate an additional $1 trillion in earnings. The same organization also estimated that racial disparities in health access in the United States represent $93 billion in excess medical care costs and $42 billion in lost productivity. These figures are expected to rise if the health disparities continue, as the United States becomes increasingly diverse.

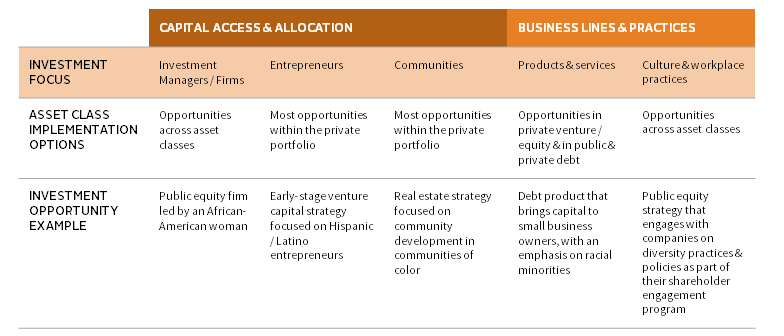

Given the complexity of racial equity, impact investors can find quite a few approaches to address the opportunity. Our view is that strategies focused on racial equity can be bifurcated into two areas. The first is increasing capital access & allocation, which seeks to increase capital flows to communities of color and address the historic and continued capital gap for those communities. The second is improving business lines & practices, which seeks to ensure that existing businesses, products/services, and policies are positively supporting communities of color. In practice, these themes are likely to overlap (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5 TWO AREAS OF RACIAL EQUITY INVESTING

Strategies focused on capital access and allocation tend to deploy capital in support of investment managers, entrepreneurs, and communities of color. Examples include tilting the manager roster toward firms that are owned and/or led by people of color, investing in a venture strategy with a particular focus on diverse entrepreneurs, or investments in critical consumer services related to health, wellness, and food systems. Notably, the types of entities supported tend to be quite varied, with only some focused on mission-aligned businesses.

Investors can support business lines and practices that benefit racially diverse populations across two primary channels: developing beneficial products and services and promoting cultures that have a positive impact on racially diverse populations. Examples include a venture capital strategy that backs start-ups that create affordable and accessible financial tools, with a focus on serving communities of color, and a private strategy that engages with its investments on having better practices and policies around diverse individuals and communities. Impact investors, via early-stage venture capital investments, can also encourage both investment managers and company leadership to entrench these practices of equity and inclusion into the fabric of the company from the earliest stage, with a goal to drive lasting change as the company moves toward a public offering.

As investors embed racial equity investments into their portfolios via the two channels described above, we encourage investors to consider four factors as they source and diligence investments. These key considerations for racial equity investing include:

- Internal culture: Has the manager adopted the same principle it espouses? Does the organization have programs/policies around diversity, equity, and inclusion?

- Cultural competency: Does the manager have the cultural know-how and acumen to address the needs of racially diverse communities?

- Connectivity with community: Are impact investors involving the community directly in the investment/decision making process and leveraging the expertise and voices of community stakeholders? If not, is that something they have expressed a willingness to consider? 3

- Risk mitigation: Are there any risks communities might bear that could run counter to an investor’s intended impact goals as a result of the strategy employed and if so, what steps can the manager and/or investor take to address them?

Given the broad swath of strategies, it’s difficult to generalize investment characteristics, such as vehicle types offered and stated return targets. Investments will vary greatly depending on an investor’s goals. We expect that the growing prominence and focus on racial equity investing will yield a more robust opportunity set, resulting from both new entrants and existing players pivoting toward the opportunity.

Putting It Into Practice

Institutional investors focused on impact inevitably ask themselves how do we maximize the impact of our investments? Unfortunately, not all investments align perfectly with an investor’s impact goal. We tend to think about the varying levels of alignment between investment strategies and impact goals as taking one of three forms—the impact is either focused, holistic, or neutral. Some investors might use just one strategy, or a combination of all three in their efforts to seek greater social equity impact alignment as the investment universe develops.

Focused Impact: These strategies align closely with an investor’s impact goals. Investors expect these strategies to generate measurable impacts and outcomes; investments are available across the return spectrum. Although the investment landscape is constantly evolving, opportunities for focused impact strategies are most frequently found in private markets, with some opportunities within public and private debt. Program-Related Investments (PRIs) are another long-standing, focused impact tool, with a range of structures available, from cash deposits and loan guarantees to catalytic funds and direct equity/debt investments. This flexible use of capital can offer greater opportunities for innovation and has been an effective way for many in advancing their social equity agenda.

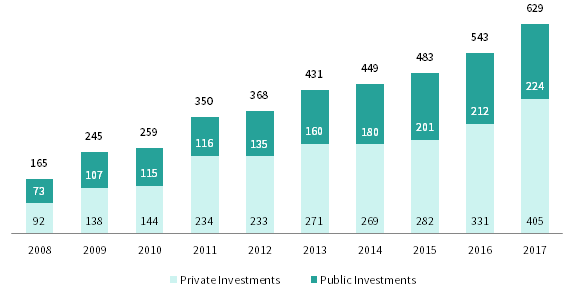

Holistic Impact: These strategies align with impact goals to a lesser degree than focused impact strategies and opportunities exist in all asset classes. In practice, however, we see investors employ this approach primarily in the public markets, where we have seen tremendous growth in the number of managers incorporating ESG factors across asset classes (Figure 6). Further, investors have the opportunity to engage managers to consider more specific social impact objectives as they assess various companies.

FIGURE 6 MANAGERS INCORPORATING ESG IN PRIVATE AND PUBLIC INVESTMENTS

2008–17

Notes: These numbers reflect the managers in our database that have been identified by Cambridge Associates as actively integrating ESG and/or impact as a core and material part of their investment strategy. The identification process is systematic, but subject to judgement. Specific composition of managers may vary each year as firms consolidate, close, or shift their approach. The methodology for identifying managers may change over time to reflect market conditions and best practices.

Neutral Impact: These strategies seek to avoid conflict with an investor’s impact goals. An example could be a passive screened public equity strategy that avoids firearms, predatory lending, and for-profit prisons. Notably, though some investors may view this choice somewhat neutrally by not wanting to profit from a certain industry, others may view this method as a powerful tool to signify their opposition. Investors can apply this lens across the portfolio, with minimal expected effect on portfolio construction and investment returns.

Investors should also note that certain investments might detract from their overall social equity impact aims. Managers may have an implicit bias against diverse people, or they may invest in businesses that negatively impact marginalized communities. These impact “risks” are present across asset classes. We encourage investors to be diligent and dig into underlying holdings and portfolio companies to ensure that the portfolio is not acting against its stated impact objectives.

When building a portfolio with a social equity lens, investors should remember that there is no “one size fits all” approach. Due to portfolio construction constraints, not all solutions or structures will be applicable or relevant for all investors. This is OK. Investors should be aware of the opportunities and limitations of their own capital pools, and take that into account as they seek to create solutions.

Conclusion

Social equity investing offers investors the opportunity to align their portfolios with their impact goals and advance solutions to some of the most pressing social issues of our time. Social equity investors can address a myriad of thematic issues such as education, health, race, or gender. We hope investors can leverage the examples provided in this report to activate their portfolios for social equity impact. To be sure, the need is great and the time is now. As the impact investing space continues to mature, we expect the opportunity set of investable strategies will grow. We encourage investors to share knowledge to support the growth of social equity investing, so together we can build a more equitable society.

Erin Harkless, Senior Investment Director

Ashley Cohen, Senior Investment Associate

Other contributors include Tom Mitchell and Danielle Reed.

Footnotes

- A definition we like is: social equity investing seeks to promote fair treatment and equality of opportunity and access for all in areas such as civil rights, freedom of speech, education, financial systems, healthy/safe communities, etc., regardless of a person’s background (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and/or socioeconomic status).

- Please see the Appendix (found in the PDF file attached to this page) for more detail on investing in social equity issue areas.

- For more details and guidance on engaging the beneficiaries in the investment process, please see Katherine Pease, “In Pursuit of Deeper Impact: Mobilizing Capital for Social Equity,” KP Advisors, 2016.