Healthcare System Investments: Play Defense Before Offense

The COVID-19 pandemic financially shocked healthcare system enterprises and investment portfolios, but those shocks were short lived and the recovery was swift. In fact, by the time 2021 ended, many hospitals were in a stronger financial position after the positive impact of stimulus funding, stabilizing operational results, and substantial investment gains. But challenges still exist. Revenue and expense pressures weigh upon healthcare margins in 2022, and many elements of delivering healthcare have changed the way hospitals plan and prepare for the future.

These complex dynamics affect liquidity needs, investment pool sizing, and portfolio strategy for healthcare providers. To implement a successful long-term investment program, a hospital system must first be clear about liquidity needs and risk tolerance. In this environment, the investment playbook may call for building a solid defense—which means right-sizing near-term and long-term assets and securing sufficient liquidity—before playing offense in the implementation of a long-term investment strategy.

Financial Pressures

Many healthcare enterprises are expecting compressed operating and cash flow margins throughout 2022, as expense growth outruns uneven revenues. According to a recent Moody’s outlook, operating cash flow could decline between 2% and 9%, primarily driven by expense growth. The most significant disruption on the expense side is staffing shortages—especially among nurses and other skilled workers. This dynamic will drive up wages and labor costs, which represented more than half of health systems’ total expenses in 2020. The staffing cost outlook is difficult, as it will require significant effort and compensation to adequately retain physicians, nurses, and staff who suffer from burnout. Supply chain disruptions, inflation, increasing drug costs, and investments in cybersecurity will only exacerbate expense escalation that will place downward pressure on margins.

Capital expenditures are also expected to increase in 2022, as many hospitals deferred projects and decreased routine maintenance to preserve liquidity in 2020 and 2021. Capital needs are shifting dramatically as healthcare delivery shifts away from traditional in-patient treatment at hospitals toward clinics, local venues, and home settings. Exponential growth is still occurring in telehealth and digital strategies. While this transition is exciting, it requires agility as higher, more complex capital spending will be calibrated on a shorter capital cycle than what healthcare systems have traditionally encountered.

On the revenue side, shifts in patient volumes and reimbursement rates may suppress revenue growth in 2022. Patient volumes have recovered to varying extents but are still subdued compared to pre-pandemic levels. More profitable elective procedures are at risk of being cancelled or postponed as the labor shortage persists. If additional COVID-19 variants arise, they could further disrupt elective surgeries and will inhibit revenue growth more. Reimbursements from insurers are likely to increase modestly and may be insufficient to keep pace with inflation and staff costs, as commercial payers are exerting more leverage in negotiating lower prices for patient care. Relatedly, Medicare and Medicaid provide lower reimbursements than commercial insurance, and revenue from these programs is steadily increasing as a share of reimbursement and as a percentage of total gross revenue.

Healthcare system balance sheets were substantially strengthened by federal and state stimulus efforts in 2020, such as the CARES Act funds. Liquidity metrics were bolstered during 2021, but additional funds are unlikely, and some of this liquidity benefit will reverse as Medicare advances are repaid between April and September. Additionally, 50% of any deferred payroll taxes from March to December 2020 are due to be repaid by the end of 2022. Taken together, these repayments will decrease days cash on hand by a projected 30–40 days in aggregate. Balance sheets will also lose the highly favorable tailwind of low-interest debt issuance as higher rates are a reality across the yield curve. While spreads are still at favorable levels, healthcare systems can expect significantly higher average coupons on issuance.

In short, many healthcare systems came through the combined operating and investment market shock of the pandemic in good financial shape, thanks in part to increasing financial strength leading up to the pandemic, strong support from the government during it, and the relative brevity of the market correction. But we don’t know exactly what the next crisis will look like. Uncertainties around operating pressures, a more prolonged market correction, and rising interest rates could challenge the financial model and access to capital markets. Given this backdrop, many healthcare systems may need to rely more strongly on reserves and investment assets to support operations and capital initiatives.

The Investment Playbook: Ensure Sufficient Defense Before Deploying Offense

If combined with a negative investment market environment, the confluence of revenue and cost pressures, capital initiatives, and balance sheet complexities could create a perfect storm of financial stress for a healthcare system. Given this risk, we recommend ensuring there is sufficient defense to weather a difficult period before playing offense with truly long-term investment assets.

The right level of defense will vary in different conditions, but taking these steps can help determine potential liquidity needs. Considerations include:

- The pace of flows from operations into the long-term investment portfolio (LTIP). With operational cost uncertainty and pandemic-to-endemic transition, what is the likelihood the pace will continue, slow, or even reverse?

- Potential capital demands on the system over the next several years (capital expenditures, possible acquisitions). Which of these which are unavoidable (or potentially unexpected)? If operating margins are compressed, or if debt funding becomes less attractive, how might the system meet those demands? Could any plans be delayed?

- In light of the above, the use of an “intermediate pool” representing potential near-term demands on the system. This can be invested in short-duration, high-quality fixed income capable of generating at least some return while the system navigates potentially choppy waters.

With an understanding of potential liquidity needs, the system can then test its assumptions with some high-level modeling to help to assess the financial impact of a combination of dynamic variables.

Putting the Playbook Into Action: A Case Study

In our case study, we use Cambridge Associates’ Portfolio Enterprise Risk (PER) model to inform a hypothetical hospital system’s decision about how much of its assets should be invested for the long term and how much should be kept in reserves. We often turn to the PER model—a projection model that incorporates operating, capital, and investment assumptions—to analyze the intersection of enterprise and investment strategy and to better understand the implications for asset sizing. In this scenario, the hospital system has $1.2 billion in assets and has determined that it may potentially need $200 million of those funds. The system is deciding whether to invest the $200 million in the LTIP to generate higher returns or to keep it in safer, short-duration investments as a cushion against an uncertain operating environment. It is helpful to analyze the decision in a shorter-term framework that matches the need for the liquidity, so we model a five-year period.

For this hypothetical hospital, operating surpluses have historically been invested in the LTIP, but the hospital’s compressed margins are now expected to break even for the next few years, limiting future contributions. Given more constrained cash flow and the potential for capital funding needs, acquisition opportunities, and possibly constrained access to debt markets, we assume that the $200 million will be needed during the five-year window of this analysis. We model withdrawals of $100 million each in years two and three, and we pair the liquidity needs with investment market stress.

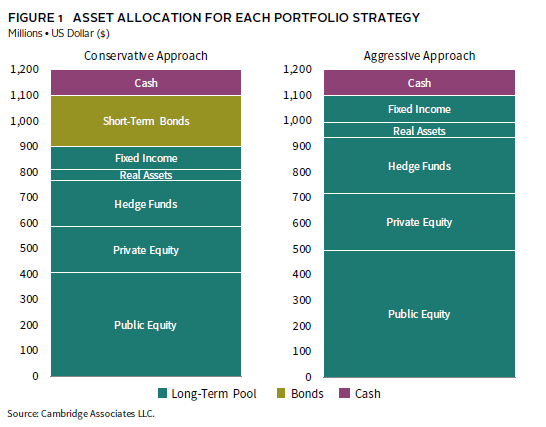

In the case study, we use the PER model to compare a conservative allocation approach with an aggressive approach. The conservative approach plays defense by placing the $200 million in a short-term bond portfolio as an added cushion against an uncertain environment, while the aggressive approach plays offense by investing the $200 million in the LTIP in hopes of earning higher returns. We assumed the short-term bond portfolio is made up of laddered bond instruments that result in an annual return of 1.2%. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the system’s aggregate asset allocation in each approach.

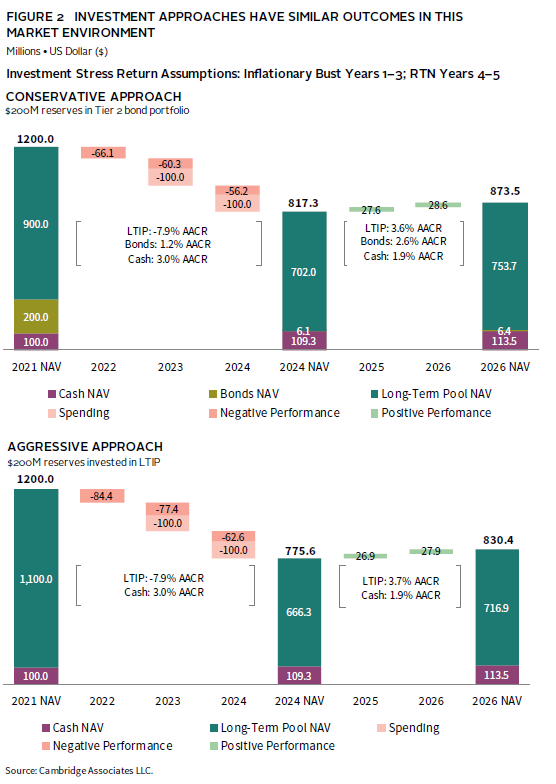

To simulate an investment stress scenario, we model three years of negative returns for both stocks and bonds using Cambridge Associates’ Inflationary Bust assumptions, followed by two years of our Return to Normal assumptions, which estimate positive, though somewhat muted performance. The result of this prolonged investment stress, even followed by two years of positive returns, is a meaningful decline in the LTIP over the five-year period. The system’s substantial declines in investable assets are exacerbated by the timing of the outflows during years of negative returns. In this investment stress scenario, the conservative portfolio’s $200 million in additional short-term reserves cushions the blow, declining 27.1%. The aggressive approach suffers a greater drop of 30.8%—a net difference of $43 million (Figure 2).

Perhaps a more direct way to look at the trade-off between the two approaches is to consider what happens to the assets in two different market environments. If the system experiences a benign market environment, in which the long-term portfolio generates positive returns (our Steady State scenario returns 6.3% annually for all five years), the aggressive approach that invests the $200 million in the LTIP generates $40 million more than keeping it in reserve. But, in this benign environment, either allocation provides ample resources for spending, with money left over to be directed however the system sees fit. The Steady State scenario assumes positive economic growth but reflects current (high) asset class valuations. The return assumptions resulted in an annualized return of 6.3% for the long-term pool over the five-year period.

However, the inflationary bust puts the risk tolerance to the test: in this environment, the conservative approach that places $200 million in the bond reserve gains in value, with money left over after spending. In contrast, the $200 million invested in the LTIP loses $30 million by the time the first withdrawal is made and even more before the second withdrawal comes out, forcing the system to dip into other funds invested in the LTIP to meet spending needs. Depending on your perspective, the $34 million gain from the more aggressive approach in a benign environment may not outweigh the pain of the $43 million loss in a more difficult one (Figure 3).

This analysis shows that the long-term investment strategy may not be the right fit for assets needed in the near term unless the hospital system can find other funds to replace the $200 million or defer spending. With that flexibility, the funds can be invested in the LTIP with a long-term time horizon and withstand short-term volatility and potential loss in value.

Every hospital system will have different sensitivities to various inputs. Developing a scenario analysis that reflects a system’s unique circumstances can help inform whether a system has the wherewithal to withstand a rocky environment in pursuit of higher return, or whether it is more prudent to shore up defenses to weather any potential storm.

Conclusion

With confidence in its defense, a hospital system can move to its long-term investment strategy to play offense. There are a few approaches that can build performance and protect needed liquidity:

- Be aware of where you’re playing offense and defense at the total enterprise level. If you have accounted for potential demands on the system outside the LTIP, it may not be necessary to increase liquidity or defensive assets within the LTIP.

- If not, consider taking a “barbell” approach to liquidity within the LTIP: maintain (or continue to build) exposure to private investments that will drive returns, but make sure your bonds are high quality, liquid, and of sufficient duration to provide a hedge against a prolonged equity downturn.

- Scrutinize “tweeners”—hedge funds or credit strategies with longer lockups—that may not offer the same bang for the liquidity buck.

There is no one-size-fits all solution when it comes to determining the sizing of assets and time horizon of investments, especially in the dynamic environment of investment markets and hospital enterprises. In this paper, we have provided examples of modeling that can help test assumptions and assess the risk and return implications of decisions in different environments. Ultimately, each hospital system needs to assess their specific conditions and tradeoffs to find the appropriate balance between defense and offense.

Billy Prout also contributed to this publication.