Navigating the AI Revolution: State of the Technology Today and Potential Future Trajectories

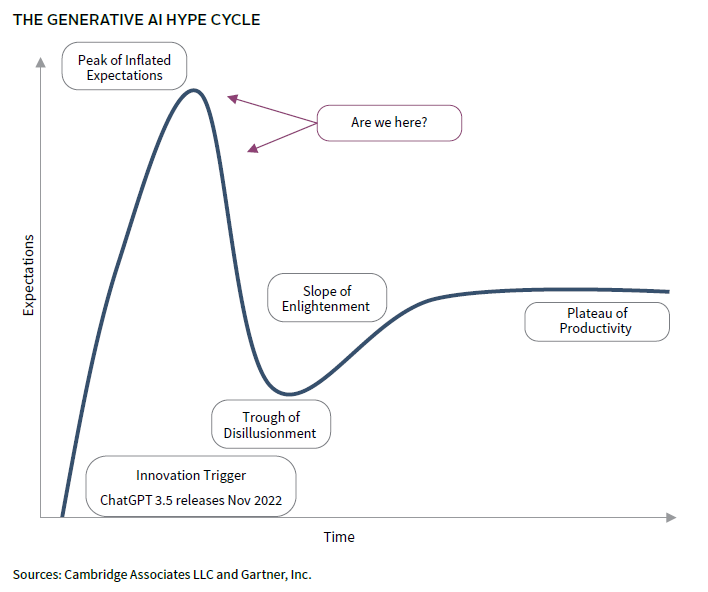

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is at a pivotal point, representing a potential “platform shift” more significant than the technological advances of the last 50 years with profound economic, societal, and geopolitical consequences. As investors navigate the flood of AI news, it is helpful to remember that a new technology’s impact is typically overestimated in the short term and underestimated in the long term. But the path of AI’s evolution is far from set and will be shaped not just according to progress in the technology itself but also by consumer and business adoption rates, regulation, and wider societal responses.

This first paper in the series introduces the current state of AI as a technology, compares its evolution to prior technological shifts, and briefly outlines future potential trajectories. Part 2 explores how AI may reshape productivity, and the market’s reaction in investment terms. Part 3 addresses the extensive implications for asset allocation and provides guidance on how investors can position themselves for the various disruptive forces that may be unleashed.

AI Today

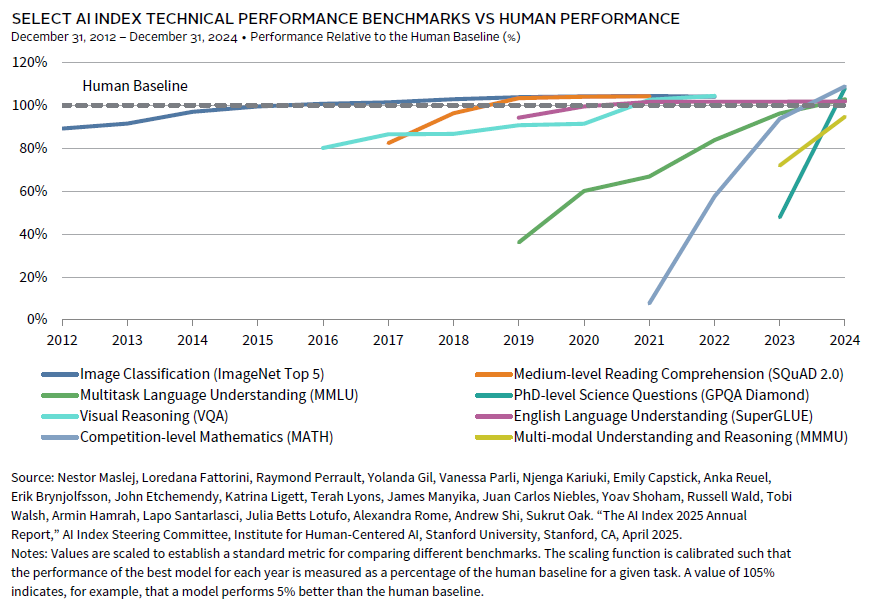

Artificial intelligence, a term dating back to the 1950s, refers to computer systems that perform tasks once thought to require human intelligence. Evolving over decades of advances—and setbacks—in machine and deep learning, AI has long been part of daily life in a number of applications, such as Google’s targeted ads. But the launch of OpenAI’s ChatGPT 3.5 in November 2022 marked a turning point. Generative AI, powered by transformer models first developed at Google in 2017, leapt to global attention with its seemingly magical powers to create and synthesize content. Compared with prior shifts, the speed at which the technology itself is evolving is unprecedented. Since 2022, model releases from OpenAI and its competitor frontier labs have come thick and fast, and the reasoning/deep research models of today represent dramatic changes in capabilities compared with early versions. Models are now multi-modal, generating not just text but images, audio, video, and music, while human voice/AI interfaces are taking shape. Meanwhile, the arrival in early 2025 of China’s reasoning model DeepSeek R1 upended the United States’ presumed unassailable lead in this era’s “space race.” More so than in past cycles, technological “moats” are being threatened and business models upended in short order.

Improvements in hardware and algorithmic efficiency are driving down the cost of basic AI inference each quarter—much faster than occurred in mobile and cloud. In fact, the inference cost for a system performing at the level of ChatGPT 3.5 dropped more than 280-fold between November 2022 and October 2024. As usage costs of models decline, the technology becomes more accessible and scalable, and tasks that were prohibitively expensive for all but the largest corporations can be run by individual users.

At the same time, the cutting-edge models still require exponentially more computing power, more energy and ever larger data sets. Estimates for the training for the next generation of frontier models run to $1 billion or more. Cloud infrastructure was expensive to build in the early days, but the capital intensity of large model training is (for now) an outlier, reinforcing oligopolistic dynamics at both the corporate and national levels.

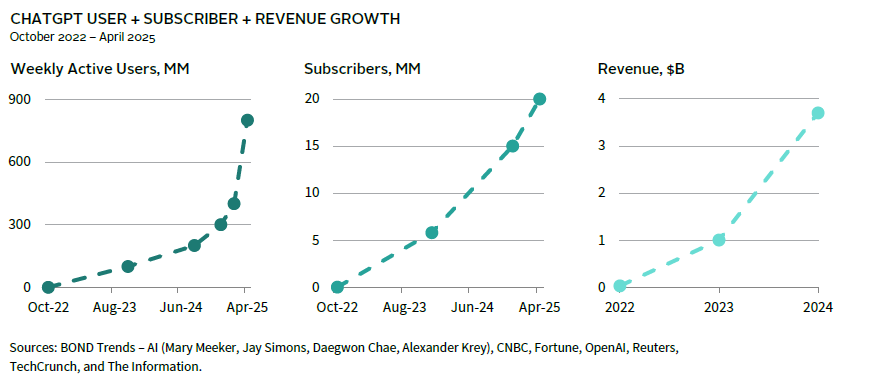

Headline rates of adoption are without precedent. ChatGPT reached 100 million monthly active users within two months of launch, which compares with 2.5 years for Instagram, 4.5 years for Facebook, and about 75 years for the fixed line telephone. In the latest data, OpenAI, founded just a decade ago, saw weekly active users scale from 300 million to 800 million since the beginning of 2025, and the firm predicts annual revenues of $12.7 billion in 2025, according to Reuters.

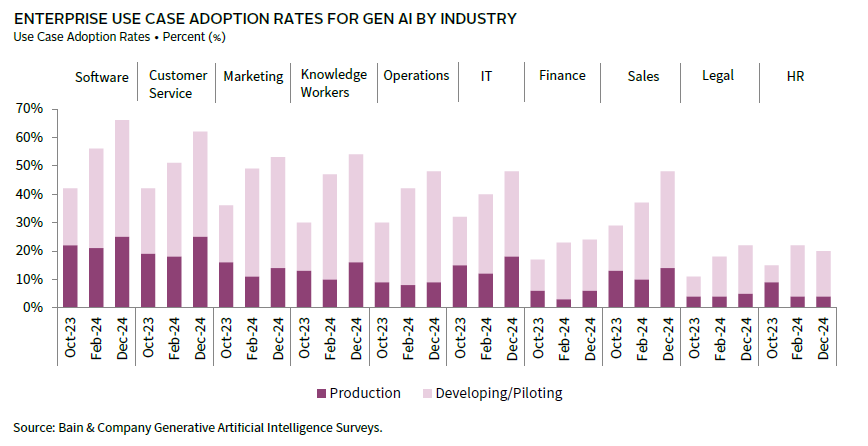

Despite the headline numbers, however, it remains early in the context of systemic adoption. The above “hockey stick” figure, impressive as it is, depicts weekly active users, and hence does not reveal usage intensity. OpenAI does not yet disclose the breakdown between consumer and enterprise customer adoption, but consumer dominates, and enterprise is widely estimated to remain a small fraction of overall activity.

In Gartner hype cycle terms, some corners of the market, notably venture, are close to the “peak of inflated expectations.” But elsewhere fundamental questions are being asked as to when big tech’s vast capital spend will translate into economic value. Models do operate at a PhD level in certain settings, but still fail at many mundane tasks. There is breakout usage in coding and customer support, and big tech, professional service, finance and retail firms lead in adoption. But in many cases, implementation remains in the pilot phase or at the partial deployment stage. A global survey by Fivetran on AI and data readiness found 42% of enterprises reporting more than half of their AI projects delayed, underperforming, or failing due to data readiness issues, highlighting the gap between ambition and practicalities.

While model “hallucination” rates (fabricated or incorrect answers) are much improved, they remain obstacles to deployment in critical enterprise, healthcare, legal, and military settings. Consumers are using the algorithms for anything from product recommendations to therapy sessions, but still await the “game-changing app” that transforms behaviors in the way that Uber and Airbnb did with the combination of mass internet adoption and the advent of the smartphone. Gartner’s “slope of enlightenment” is still around several corners.

AI’s Future Potential Trajectories

The future course of any technology is typically opaque, but the trajectory for AI appears especially unpredictable. On the one hand, it seems unlikely that AI simply fizzles, along the lines of other supposed breakthroughs such as the metaverse that was going to be the next iteration of the internet. However, whether AI will truly transform the economy and science as a general-purpose technology with the import of electricity—without unleashing untold harms—remains unclear even to the experts.

Front and center in the “space race” is the sprint to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—although no one quite agrees on what AGI is, or what exactly we will do with it when we have it. To the optimists, it is either actually here or close, with Dario Amodei, Anthropic CEO, heralding systems that are “smarter than most Nobel Prize winners” before 2030. Meta’s Yann LeCun, by contrast, argues that large language models will never achieve AGI, let alone “superintelligence,” and that a wholly new architecture is required. Today, the latest reasoning models may exceed broad human intelligence along certain vectors, but, to the skeptics, appear far from living up to the ambitions for AI to solve humankind’s biggest challenges.

While the frontier labs reach for the AGI stars, a few near-term developments should be firmly on investors’ radars, including the rise of AI agents and the early days of generative AI’s interactions with the physical world.

“Agentic AI,” namely what happens when AI is given agency, denotes systems that can execute defined tasks autonomously, rather than just answer questions (as a chatbot does). Coding agents have seen fast adoption by software developers, while non-technical users can use natural language to generate code for applications or websites. Another example, from the legal world, is an agent that drafts documents and automates negotiations. Consumer applications currently lag enterprise applications, but there are attempts at agents that shop, and we are promised personal bots that will know us deeply, organizing our files and our lives. If the formidable challenges around accuracy, privacy, and security can be overcome, agents could become productivity gamechangers, as well as formidable disruptive forces. The “agentic economy” with agents rather than humans crawling and interacting with the web, could disintermediate swathes of the existing online economy, while automated workflows threaten traditional Software as a Service (SaaS). So far, agents are still mainly copilots rather than autonomous, and developments from here go to the heart of the fundamental questions about our future with AI, including which tasks are suitable for full automation, and which are on a spectrum where AI augments human capabilities to a greater or lesser extent.

Meanwhile, “physical AI,” including robotics, is moving up the agenda. As the slow progress in autonomous vehicles demonstrates, hardware dependent innovations move much more slowly than those dependent on software. Impediments range from physics to capital intensity, to adoption hesitancy. But advances in generative AI, in reinforcement learning and in edge AI (smaller models able to run locally), are behind developments making robots more effective and more capable of autonomous planning and decisions. China, the leader in industrial robotics for years, is advancing in humanoids and aims to start mass production this year. Meanwhile, the United States is playing catch-up. Elon Musk promises one million Tesla Optimus humanoid robots by 2030, but the fact that much of the global supply chain is in China is a notable handicap. Whether specifically “humanoid” robots are an overhyped distraction or not, the latest robotics advances aim to rearchitect industry, agriculture, healthcare, defense, and more.

As investors look farther out, they should consider the extent to which AI’s future course will be shaped by factors beyond the development of the technology. AI is currently advancing at a pace that outstrips society’s ability—or willingness—to adapt. These factors include:

Rates of adoption. It is worth remembering that nearly half of the world’s banking systems still use COBOL, a 1960s programming language, and many healthcare systems still rely on fax machines—a suitable counterweight to the more optimistic forecasts about the pace of AI adoption.

Implementing new enterprise systems not only involves serious software and hardware investment, but often requires significant change to human work habits. Predictions of adoption have frequently been ahead of reality in prior technology shifts. Indeed, the more quickly a wave develops, the more it can overwhelm, and itself reinforce inertia. At the very least, rates of adoption will be nuanced by industry, by size of business (large enterprise versus SMB, regulated versus not regulated), and by geography. On the consumer side, various forms of backlash may arise due to ethical and safety concerns. Even now, amidst all the AI fever, an “analog revival” movement is building, spurred by digital fatigue and centered, ironically enough, in Silicon Valley.

UBI – or Not so Fast? In September 2024, Vinod Khosla predicted that within five years AI would be able to perform 80% of the work in 80% of all jobs. AI is certainly the first technology wave in which knowledge workers are squarely in the line of fire. Will it also be the first not to create net new jobs? The conversation about where AI automates and where it augments, and hence the extent of job displacement, has barely begun. Many corporate leaders remain coy about their immediate intentions, even if they have begun to formalize strategies. Citing Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a one-stop solution to job destruction, the techno-optimists tend to gloss over the forces of worker resistance, the scope for government interventions to implement labor protections, and, indeed, the ills of automation overreach.

Responsible AI. As AI godfather Geoffrey Hinton sees it “we are like somebody who has this really cute tiger cub. Unless you can be very sure that it’s not gonna want to kill you when it’s grown up, you should worry.” The development of this highly consequential technology is currently largely in the hands of startlingly few people at the top of frontier labs and big tech, leaving regulators on the back foot. In prior waves, regulatory frameworks evolved gradually, but the speed at which AI is moving, combined with its centrality to geopolitical rivalries, creates a policy minefield. To date, major divergences are appearing, along political and cultural lines. The 2024 EU AI Act is the world’s first major legislation, classifying AI systems according to risk and by human rights, with its prioritization of safety over speed of innovation. The current US administration’s contrasting market-based approach has seen the meager regulation that was in place largely rolled back, and, while initiatives continue in various states, innovation and dominance over China appears to be the priority at federal level. Meanwhile, China’s state-led approach rests on tight control to maintain domestic societal stability, combined with multifaceted initiatives in pursuit of its own ambitions for global dominance.

The energy conundrum. Pick your statistic as to how energy intensive AI currently is. Its voracious energy demands are major themes for investors to invest behind—from ways to improve model energy efficiency, to the funding of new clean energy supply. But at a high level, progress will be accelerated or otherwise impacted by individual countries’ responses to bolstering their power infrastructure, and national competitive advantages shaped by how the energy story unfolds. China is investing massively not just in AI infrastructure, but in the energy resources to support it, and is expected to become the world’s leader in installed nuclear capacity by 2030.

The “cute tiger cub” is growing up fast, and while AI’s cheerleaders likely overestimate the speed with which the AI revolution is “remaking everything” as Marc Andreessen put it recently, the evidence is clear. Those who embrace AI thoughtfully, understanding both what it can and what it can’t do, will be best placed to thrive in the years ahead. The following two pieces are designed to help clients think through the consequences, and both position themselves for the opportunity as well as build resilience into their portfolios for the range of potential outcomes.

Drew Boyer, Graham Landrith, and Jack Terrett also contributed to this publication.

Katharine Campbell - Katharine Campbell is a Partner for the Endowment & Foundation Practice at Cambridge Associates.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50+ years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients achieve their investment goals and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.