Navigating the AI Revolution: AI’s Far Reach in Shaping Asset Allocation Opportunities

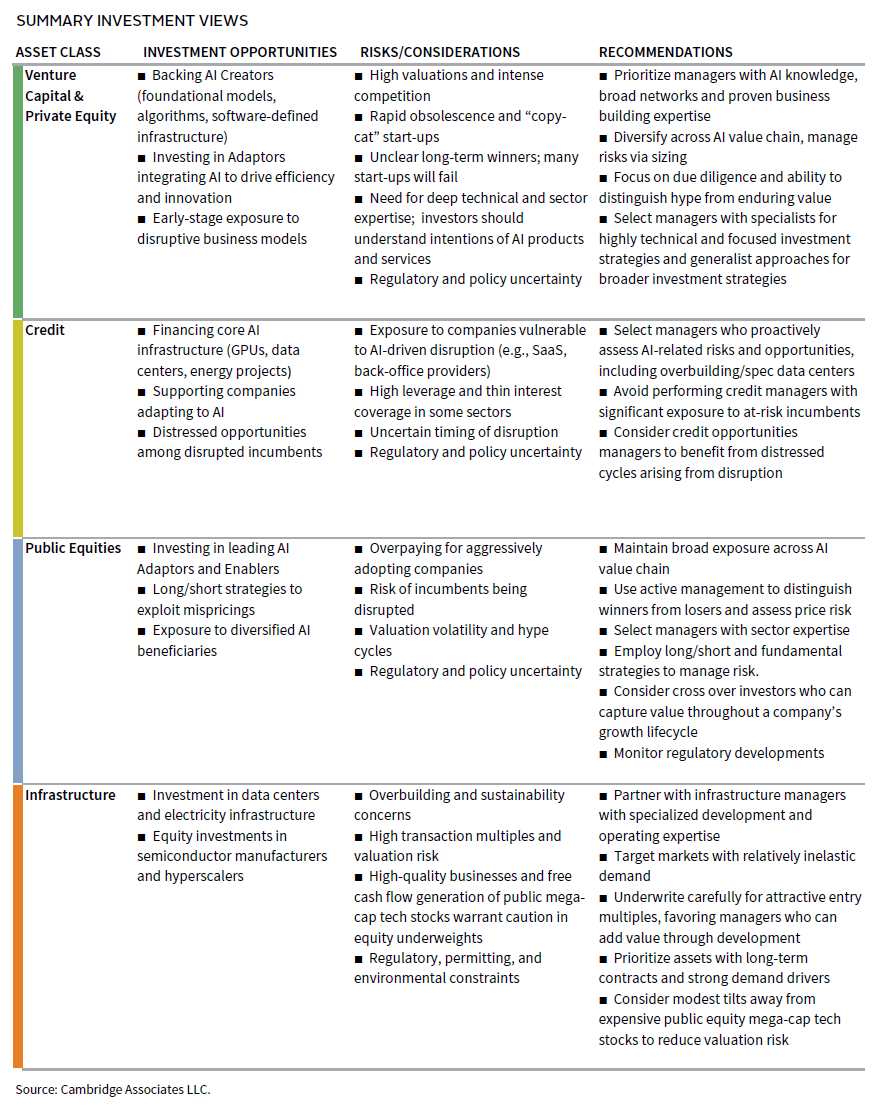

Generative AI marks a pivotal moment in AI, with the 2022 public release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT as a major milestone. As discussed in Part 1 of this three-part series, AI is a transformative technology paradigm that will continue to evolve over the next decade and beyond. While significant investment has fueled rapid growth in AI and its supporting infrastructure, we are still in the early stages of this innovation cycle. As explored in Part 2, the rapid adoption of AI is also beginning to unlock new productivity gains, though widespread economic impact is still emerging. In this piece, we explore AI’s transformative potential for asset allocation opportunities and risks, as well as key implementation considerations and challenges. Investors should be actively considering how to prudently achieve exposure across their portfolios to the AI technology, the infrastructure required to deploy AI, and the companies that will benefit from the power of AI, while remaining vigilant to the risks of disruption, overvaluation, and overbuilding.

Investment Implications Through The Tech Cycle

To navigate the AI investment landscape, it is helpful to segment the market into five archetypes that capture the diverse ways in which companies interact with AI:

- Creators are the pioneers at the frontier of AI innovation—companies developing foundational models, advanced algorithms, the software development toolchain, and specialized hardware that form the core of the technology.

- Disruptors create a transformative change that goes beyond integrating technology into an existing process, launching new business models that were unimaginable prior to the technological leap (e.g., Uber or Amazon of the internet era).

- Enablers provide the essential physical infrastructure that makes AI possible, including semiconductors, data centers, and energy solutions.

- Adaptors are businesses that integrate AI into their operations, harnessing its power to drive efficiency, unlock new business models, expand their market share, and maintain competitive advantage.

- Finally, the Disrupted are incumbents whose market share or relevance is threatened by the rise of AI-powered competitors.

Each of these archetypes presents distinct investment opportunities and risks across asset classes.

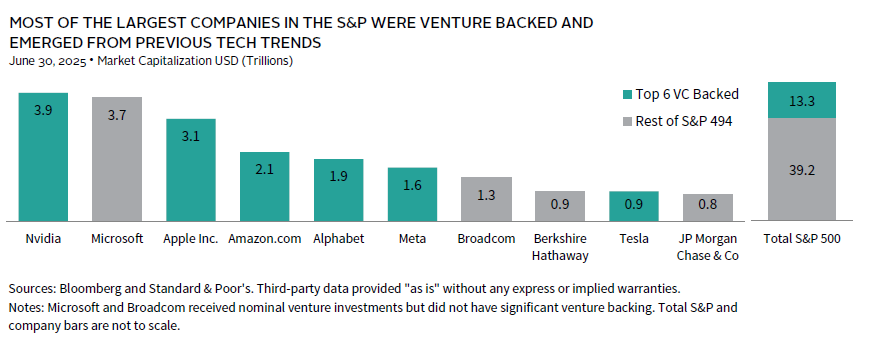

As discussed in Part 1, where we highlighted past technology cycles, this framework echoes the dynamics of the internet era that launched the information age. During that period, Apple, Google, and Microsoft were among the creators, building the platforms and software that defined the new economy. Amazon emerged as a disrupter, fundamentally changing the retail landscape. With the emergence of cloud computing, software-defined infrastructure was developed to manage or enable compute, storage, and networking through software. Companies like Intel and Cisco served as enablers, providing the chips and networking equipment that powered the digital revolution. Today, as AI ushers in another wave of transformation, understanding where companies sit within this cycle is essential for identifying both risks and opportunities across the investment landscape.

Creators and Disruptors

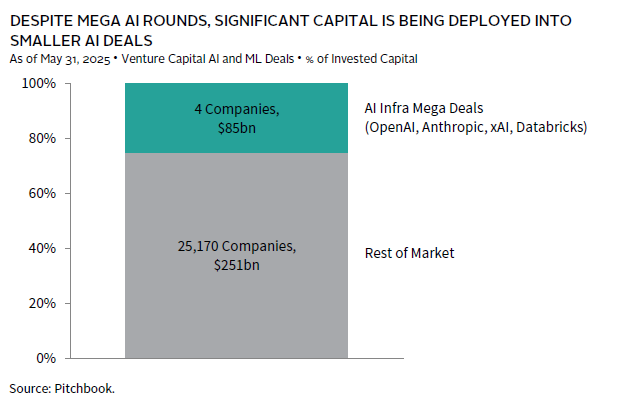

Venture capital (VC) remains a crucial funding source for innovative start-ups engaged in high-risk research and product development. This dynamic drove previous technology waves, such as the internet, mobile, and cloud computing. However, the AI era presents a different landscape. Unlike the cloud era—where established companies were slow to adapt and start-ups captured early gains—many incumbents are now early AI leaders. These companies are cloud-native and deeply integrated into corporate systems. They leverage their scale and distribution to build AI capabilities internally or accelerate innovation by acquiring or investing in VC-backed AI start-ups. Notable examples include Google’s acquisition of DeepMind (which powered Google Brain and Gemini), Microsoft’s early partnership with OpenAI, and Amazon’s partnership with Anthropic. Hyperscalers’ capital expenditures have been extraordinary and are expected to continue as AI technology advances. Key areas of VC investment include large language models (LLMs), supporting software infrastructure, and “applied AI” applications built on this foundation.

As outlined in Part 2, VC investment in AI has reached record highs, with intense enthusiasm and abundant capital pursuing a limited number of high-quality start-ups. Adoption rates have surged across many companies (see Part 1), but much of the early revenue is “experimental,” reflecting trial phases rather than sustainable businesses. This momentum has spurred a wave of new company formations and AI strategy announcements, creating significant “AI noise” in the market. Interest is also growing in “physical AI,” where AI intersects with industries such as manufacturing, construction, healthcare, and aerospace and defense. However, all this frenzy has led to inflated valuations, intense competition, and overfunded segments given its relative infancy. Although AI-first companies have seen rapid revenue growth, its durability is uncertain due to the experimental nature of adoption and the lack of strong competitive moats—even companies with $50 million–$100 million in revenue can be overtaken whereas in prior cycles that typically signaled victory. While a few leaders have already created significant value, many AI start-ups are likely to fail due to oversaturation, poor management, and rapid sector evolution.

Historically, major technology shifts often result in commoditization, and it is rarely clear at the onset which companies will ultimately succeed. The winners are typically those that either build on existing technology through innovation or leapfrog older products and services entirely. For instance, Dell Technologies initially dominated the PC market, EMC led in on-premises enterprise data storage before the transition to cloud solutions, and Cisco was the leader in network hardware before the rise of software-defined networking. AI is likely to follow similar patterns, with rapid change and innovation making it difficult to identify long-term leaders. As open-source competition and verticalized alternatives have driven SaaS commoditization, so too will these forces and the broader open-source community drive further innovation and disruption in AI. Despite these uncertainties, we expect long-term VC returns in AI to remain attractive.

Who will be the winning investors? We recommend diversifying across the AI value chain and managing risks through careful position sizing. Investors should prioritize general partners (GPs) with deep sector expertise, particularly at the foundational and network infrastructure levels, and a proven track record of business building. This expertise—whether within specialist or generalist firms—enables better deal flow, talent identification, and assessment of technical merit. Select specialists for investments where technology risk is high, and generalists for broader investment strategies, leveraging the strengths of both. As AI becomes more widespread and many start-ups incorporate it into their products, investment decisions will increasingly focus on how AI is applied rather than on the technology itself. This trend mirrors previous technology cycles, where, as markets matured, investment success depended more on careful selection and curation than on technical expertise. Many GPs focused on AI are relatively new and still gaining investment experience, given the technology’s rapid rise in prominence. Large generalist firms have captured many early AI successes, often partnering with specialists to combine strengths. These generalists offer larger capital pools, enabling them to support AI start-ups through multiple funding rounds, provide customer access, and offer business-building expertise. Their broad go-to-market and business development capabilities help start-ups as they scale.

Enablers

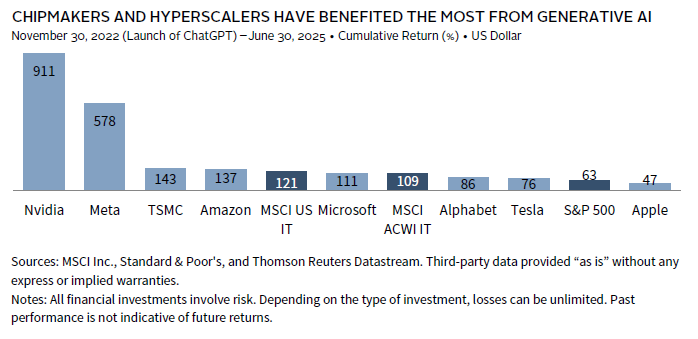

Enablers are the backbone of the AI revolution, providing the physical infrastructure that supports AI’s rapid expansion. The primary beneficiaries to date have been semiconductor manufacturers (especially those producing AI chips), hyperscale data center operators, and the power and utility companies that support this ecosystem. However, the scale and speed of investment in these areas have raised concerns about sustainability, valuations, and the risk of overbuilding—reminiscent of the internet era’s fiber optic boom and bust.

The rise of generative AI and LLMs has driven unprecedented demand for high-performance chips, particularly GPUs and custom AI accelerators. Companies like Nvidia, AMD, and emerging players such as Cerebras have seen orders and backlogs soar. Supply constraints and technological leadership have enabled leading chipmakers to command premium pricing and margins. Dominant players, especially Nvidia (through its CUDA platform), are building integrated hardware-software ecosystems, creating high switching costs and network effects, but also raising antitrust concerns. Valuations remain high, with Nvidia trading at a forward price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 32.3, as of June 30, 2025. While this is below 2024 peaks, it remains vulnerable to correction if AI adoption slows, or competition intensifies. As such, consider modest tilts away from expensive public equity mega-cap tech stocks to reduce valuation risk and enhance portfolio diversification.

Data centers are also major beneficiaries, driven by AI, ongoing cloud adoption, and rising data usage. McKinsey estimates data center capacity demand will grow at an annual rate of about 20% through 2030, with generative AI data centers accounting for a small, but growing share of new demand. Investors should partner with infrastructure and real estate managers with specialized development and operating expertise that are well-positioned to benefit from this supply/demand imbalance. However, transaction multiples have risen materially, averaging 25x EBITDA over the last four years according to Infralogic, compared to a 13.5x average for private infrastructure more broadly. This makes careful underwriting essential for attractive returns. Like other AI infrastructure assets, data centers face risk of overbuilding, as well as regulatory and environmental concerns and constraints such as local opposition and permitting delays. These risks can be mitigated by focusing on managers who can develop assets at lower multiples (e.g., low double-digit EBITDA) and sell into a strong market, often with long-term contracts from investment-grade hyperscalers (e.g., Microsoft, Amazon) seeking development partners. In contrast, speculative and remotely located data centers with more limited utility face heightened risks. From a portfolio construction perspective, data centers offer lower expected returns than private investments in innovative AI firms but can provide returns competitive with broad equities (e.g., 15%–20% target gross IRR) with diversification benefits.

Other enablers, such as utilities and grid infrastructure, have also seen increased demand and capital inflows driven by electrification and digitization trends. McKinsey expects global data center capacity demand between 2025 and 2030 to drive investment in power (including generation and transmission) to total between $200 billion (constrained momentum) to $600 billion dollars (accelerated demand), with $300 billion as their baseline for continued momentum. US on-grid electricity demand is expected to increase 2%–3% per year through 2030 up from virtually flat growth over the last decade, with faster growth in Asia (from a lower base) and slower growth in Europe. While difficult to estimate, rapid AI adoption and potential onshoring in the United States could further boost energy demand. Although AI energy efficiency is expected to improve, associated cost reductions may spur broader adoption, likely resulting in net energy demand growth. Investment in essential electricity infrastructure with inelastic demand is critical. Data centers require reliable power, necessitating redundant infrastructure such as back-up generators and batteries.

All enabler segments have strong growth potential, with chips and data centers experiencing the fastest expansion, but they also trade at heightened valuations and have the greatest exposure to overbuilding. Scale, technological edge, strong customer relationships, and specialized expertise are critical for managing these risks.

Adaptors and the Disrupted

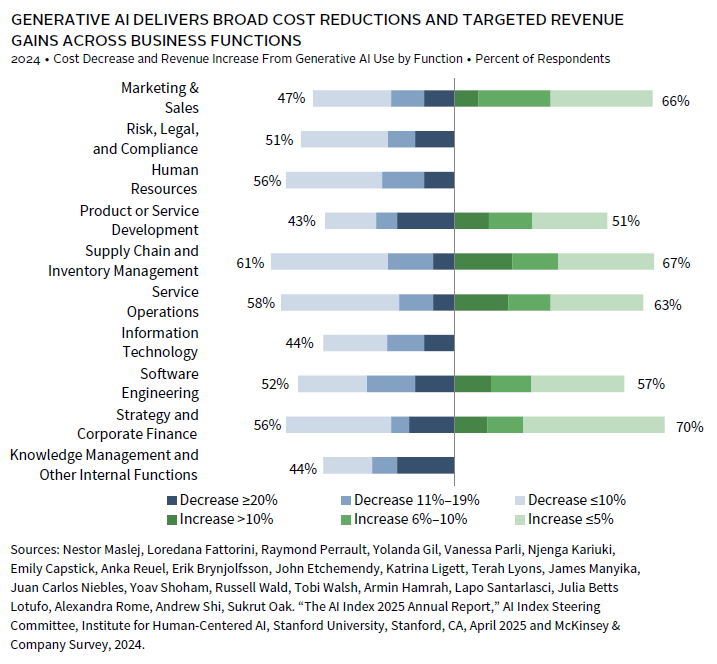

Building on the productivity themes from Part 2, growth equity and private equity-backed companies are increasingly using AI to boost revenue and improve margins. As private entities, they have more flexibility to integrate and scale AI across operations, though successful implementation requires careful execution. While many companies are still experimenting, some are already seeing early benefits in product enhancements and margin gains.

Private equity investors are actively assessing both the opportunities and risks AI brings to their portfolio companies and industries. They look for cost savings through automation (e.g., customer support, onboarding, coding) and revenue growth from AI-driven products (e.g., sales planning, demand forecasting). At the same time, they remain cautious about risks, such as commoditization (e.g., graphic design, digital marketing) and increased competition from low-cost automation (e.g., auditing, document preparation, call centers). Technology-focused managers have an edge due to sector expertise, but both specialist and generalist firms are hiring AI talent to support investment teams and portfolios. The full impact of AI will unfold over time as new use cases and broader adoption and understanding of AI technologies and their impact continue to emerge.

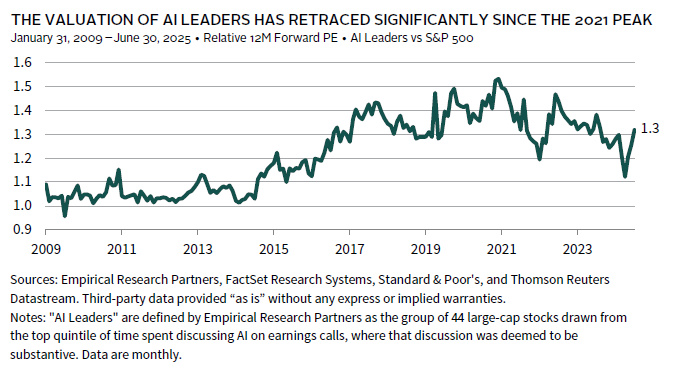

Similarly, public companies must adapt to AI or risk disruption. Investors should focus on active management to distinguish winners from losers and to assess price risk, selecting managers with deep sector expertise. Employ long/short and fundamental strategies to manage risk and exploit valuation dislocations. Public investors face the challenge of avoiding overvalued AI leaders while not overlooking lower-priced companies that may lag behind. Many leading public companies are cloud-native and well-positioned for AI, but investors should consider the entire spectrum of innovators and disruptors. Public market valuations for AI-enabled companies have dropped from their late 2021 peak; forward P/E ratios relative to the S&P 500 Index hit a nine-year low earlier this year, and have since rebounded, but remain below recent historical spikes. This environment favors long/short managers that can identify mispriced companies amid the current AI hype.

As outlined in Part 1, we recognize that non-technological factors—particularly regulatory and policy uncertainty—are increasingly shaping both the AI investment landscape and broader societal outcomes. The concept of Responsible AI (RAI) is gaining more attention as generative AI models and systems grow in complexity and become more deeply embedded across industries. RAI frameworks address the development and deployment of LLMs and broader AI applications, emphasizing principles such as fairness, transparency and explainability, accountability, privacy, safety, and security. From an investment perspective, effective governance is inherently complex, intersecting regulatory, ethical, technological, and human considerations. This complexity necessitates cross-disciplinary collaboration and often involves navigating trade-offs and misaligned incentives. As AI adoption accelerates, reported incidents of ethical misuse have increased in recent years. A recent survey found that only 14% of businesses have dedicated AI governance roles, yet 42% reported improved operations and 34% noted increased customer trust due to RAI policies and investments. 1 Companies should proactively assess, and address financially material risks associated with neglecting RAI practices, such as regulatory actions or erosion of their societal license to operate, which could result in negative commercial consequences. Governments worldwide are trying to address complex issues like data privacy, algorithmic transparency, antitrust, and national security, and new regulations could significantly impact sector competition. Investors must also monitor regulatory developments closely, as evolving rules and policies will likely influence long-term value creation and competitive differentiation in the rapidly evolving AI sector.

The “AI noise” phenomenon extends beyond private investments. Most technology companies now market themselves as AI-focused, and those that do not, risk appearing outdated. Enterprise software incumbents with high switching costs, complex technology, and strong innovation pipelines may continue to thrive, while agile start-ups can exploit weaknesses and expand from niche solutions into strategic adjacencies, potentially displacing incumbents. For example, it is unclear whether established security firms will lead in AI security or whether nimble start-ups will secure the AI/ML software supply chain. ServiceNow, a leading enterprise software provider, has thus far demonstrated successful AI adoption by leveraging its integrated suite and existing customer base to pivot toward AI-driven solutions. Given the rapid pace of change, both long-only and long/short hedge funds can find alpha by capitalizing on short-term disruptions and mispriced companies. Valuation-based and fundamental short strategies remain relevant, though it can be difficult to short declining businesses that retain temporary relevance or to identify companies prematurely dismissed as AI losers. Investors should consider managers with crossover expertise—spanning both public and private markets—as they are well-positioned to capitalize on rapidly evolving AI developments by spotting trends in private markets before they are reflected in public market valuations, and can continue to invest post IPO.

AI-related risks and opportunities are increasingly influencing credit markets. Credit managers are financing core infrastructure—such as GPUs, data centers, and energy projects—while also supporting the broader AI ecosystem. Several large managers are establishing dedicated asset-backed finance teams and raising capital specifically to pursue these opportunities. Direct lenders, in particular, have significant exposure to technology and business services, which will need to adapt in response to AI advancements.

More broadly, credit managers must evaluate the adaptability of their portfolio holdings. Many software companies—particularly those with high leverage and business models vulnerable to AI automation (e.g., HR, legal, accounting, and other back-office SaaS providers)—face considerable disruption risk. The past decade’s low-rate environment led to aggressive leverage and high valuations, leaving some companies with thin interest coverage and little margin for error. These firms are especially vulnerable if AI-driven disruption erodes their revenue base. Should AI agents automate or disintermediate core functions, revenue models may be cannibalized, and even modest declines in topline revenue could threaten debt service capacity.

Some credit managers are proactively encouraging portfolio companies to adopt AI, aiming to drive efficiencies and mitigate disruption risk. Lenders are increasingly evaluating management’s AI strategy as part of their underwriting process. Companies that successfully integrate AI may improve margins and creditworthiness, while laggards risk being left behind. As disruption accelerates, a wave of distressed opportunities may emerge among over-levered incumbents unable to adapt to AI-driven change. However, the timing of this transition is highly uncertain: some companies may be “slow melting ice cubes,” experiencing gradual market decline, while others may yet adapt successfully.

Investors should select credit managers who proactively assess AI-related opportunities and risks, including overbuilding in data centers and other infrastructure, while proactively managing exposure to incumbents in sectors vulnerable to AI disruption, such as highly leveraged back-office SaaS providers. Credit opportunity managers may be best positioned to benefit from distressed cycles arising from AI-driven disruption, as these managers can capitalize on market dislocations.

Investors should question managers on their approach to AI, both in terms of portfolio company adaptation and exposure to AI-related risks and opportunities, as part of ongoing due diligence.

Conclusion

AI is fundamentally reshaping the investment landscape, presenting both extraordinary opportunities and new risks across asset classes. The technology’s reach extends from the innovators building core capabilities, to the enablers providing critical infrastructure, to the adaptors and disrupted incumbents navigating a rapidly changing environment. Although substantial investment has already driven rapid growth in AI and its supporting infrastructure, we remain in the early stages of this technological shift, which is expected to evolve over the next decade and beyond. In previous technology cycles, the initial investments and returns from foundational innovation were ultimately surpassed by the gains generated by disruptive companies. These disruptors leverage the established or rebuilt technology infrastructure and benefit from network effects as commercial adoption accelerates, enabling them to redefine industries or create entirely new markets and business models. Attractively valued companies that can leverage AI to improve their profitability should also benefit meaningfully.

Investors should strategically seek opportunities to incorporate AI Creators, Disruptors, Enablers, and Adaptors within their portfolios, all the while maintaining a careful watch on potential disruption risks and the possibility of inflated valuations and overbuilding. Investment success in this new era will require investors to combine deep sector expertise, rigorous due diligence, and a willingness to adapt as the technology and its applications evolve. Investors that partner with managers that can distinguish between hype and enduring value, anticipate regulatory shifts, and identify the true drivers of sustainable growth will be best positioned to capture the far-reaching potential of AI in shaping asset allocation for years to come.

The MSCI ACWI Information Technology Index includes large- and mid-cap securities across 23 Developed Markets (DM) countries and 24 Emerging Markets (EM) countries. All securities in the index are classified in the Information Technology as per the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®). DM countries include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. EM countries include Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

The MSCI US Information Technology Index is designed to capture the large- and mid-cap segments of the US equity universe. All securities in the index are classified in the Information Technology sector as per the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®).

The S&P 500 Index includes 500 leading companies and covers approximately 80% of available market capitalization.

Grayson Kirk, Graham Landrith, and Archie Levis also contributed to this publication.

Footnotes

- Nestor Maslej, Loredana Fattorini, Raymond Perrault, Yolanda Gil, Vanessa Parli, Njenga Kariuki, Emily Capstick, Anka Reuel, Erik Brynjolfsson, John Etchemendy, Katrina Ligett, Terah Lyons, James Manyika, Juan Carlos Niebles, Yoav Shoham, Russell Wald, Tobi Walsh, Armin Hamrah, Lapo Santarlasci, Julia Betts Lotufo, Alexandra Rome, Andrew Shi, Sukrut Oak. “The AI Index 2025 Annual Report,” AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, April 2025 and McKinsey & Company survey 2024.

Celia Dallas - Celia Dallas is the Chief Investment Strategist and a Partner at Cambridge Associates.

Theresa Sorrentino Hajer - Theresa Hajer is Head of US Venture Capital Research and a Partner at Cambridge Associates.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50+ years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients achieve their investment goals and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.