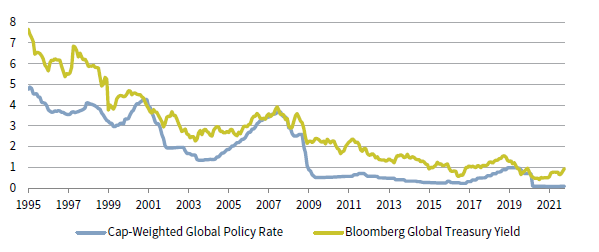

Government Bond Yields Are Likely to Rise as Central Banks Remove Support

Long-dated government bond yields rose in 2021 on strong economic growth and surging inflation. Central banks have maintained their easy money policies despite the rapid recovery in economic conditions, likely keeping yields lower than they would have been otherwise. This may soon change now that several major central banks are starting the process of dialing back support. Most notably, the Fed began tapering asset purchases in November, and its first rate hike could come as early as mid-2022. Some central banks have already started hiking rates (e.g., New Zealand, Norway), while others (e.g., United Kingdom, Canada) are expected to follow suit soon.

TREASURY BOND YIELDS SHOULD RISE WITH POLICY RATES

January 31, 1995 – October 31, 2021 • Percent (%)

Sources: Barclays Bank PLC, Bloomberg Index Services Limited, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Data are monthly. The Cap-Weighted Global Policy Rate includes developed markets countries with a weight of more than 1% in the Bloomberg Global Treasury Index and is calculated based on their respective market capitalization relative to the total market capitalization of the modified index.

The case for higher government bond yields is also supported by the likelihood that yields in most developed markets are still too low relative to underlying economic conditions, even after accounting for central bank policies. Ten-year US Treasuries were yielding 1.43% as of November 30, which is still near the lower end of our growth-implied fair value range of 1.4%–3.0%. While US nominal growth is expected to fall to 8% in 2022 from an anticipated 10% in 2021, it is still predicted to outstrip the 4% average rate of growth since 2000.

Above-trend nominal growth and the start of policy normalization will likely push yields higher in 2022. However, their path will likely be uneven, and the magnitude of any rise will probably be limited given central banks intend to move extremely cautiously. The ECB, for example, continues to push back against expectations of rate increases, and Fed officials are currently forecasting a relatively shallow hiking cycle and a long-run neutral rate of just 2.5%. In the past, the Fed’s estimate of the long-run neutral rate has acted as an anchor on the ten-year yield. Stronger-than-expected real growth and inflation could force central banks to revise the path of policy rates higher, which would increase the upside for yields. Yet, macro uncertainty is a two-way risk—unforeseen events or too much tightening too soon could dent growth and send yields lower.

TJ Scavone, Investment Director, Capital Markets Research