Brexit Update

When the white smoke emerged from Brussels and London on 24 December 2020, it was tempting to regard the agreement reached between the EU and United Kingdom as the conclusion to a process that began back in June 2016. It is certainly a historic milestone, providing much-needed clarity for many people and businesses in the wake of the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the EU. However, in the greater scheme of their future relationship, it would be fairer to say it represents the end of the beginning rather than an end in itself. Nonetheless, with the lingering threat of a tumultuous no-deal exit now removed, the headwind that this represented to the performance of UK assets has now subsided. As with other markets that have a cyclical and value bias, we believe that UK equities stand poised to benefit from the normalisation of economic activity as COVID-19 vaccines are rolled out. This expectation contributes to our tilt toward global ex US equities and away from US equities. 1 at a minimum was likely, meaning that most can carry on with much of their cross-border business. Talks are ongoing with respect to drafting a memorandum of understanding that would guide future cooperation in the area, with a goal of agreeing a text by the end of March.

The notion of a ‘level playing field’ 2 was a red line for the EU entering these negotiations. As a result, while both sides remain free to set their own standards in these areas, they risk endangering their access to the other markets if they choose to do so. In the event of such a dispute, the matter will be referred to an independent arbitration panel. This mechanism is consistent with one of the United Kingdom’s red lines, namely that the European Court of Justice no longer has jurisdiction in the United Kingdom.

Political Contagion Quelled (For Now)

The signing of the TCA will likely reduce political uncertainty in the short term. In the case of the United Kingdom, the negotiated agreement was passed with broad parliamentary support. Taken together with the fact that the Conservative party holds a sizeable majority of seats in Parliament, this should pave the way for a period of political stability that contrasts with the prior five years in which three general elections were held. For the EU, member states showed surprising levels of solidarity and cohesion when it came to the negotiation process. More importantly, though, the European Commission stuck to its red lines. This sent a message to other would-be leavers that there will be no trade free lunch outside of the EU.

Over longer horizons, however, several issues still have the potential to fester. The Scottish National Party enjoys a strong lead heading into the Scottish parliamentary elections, continuing to push the case for independence given 62% of Scottish votes cast in the Brexit referendum were for ‘remain’. The Conservative majority means it’s likely not an issue for this parliament, but it will continue to be a prominent political football. The TCA also creates an effective customs and regulatory border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which has already raised hackles in some quarters. The growing interdependence of Northern Ireland and Ireland may have implications for the future political status of the former. For EU members states, meanwhile, there will be a protracted period of ‘wait and see’ while appraising what the United Kingdom makes of life outside the union. If the divorce eventually appears to have benefitted the United Kingdom, it may yet embolden other would-be leavers.

Economic Impact on the United Kingdom

UK growth during the next couple of years is likely to be dominated by the impact of COVID-19 rather than Brexit. The country suffered the steepest decline in activity of any of its peers, and as such, it has the most scope for a big bounce. Analysts forecast UK growth will be 4.6% and 5.7% in 2021 and 2022, respectively, versus 4.0% and 3.4% for developed markets more broadly, according to median Bloomberg estimates. If the country maintains the lead it currently enjoys in the administration of COVID-19 vaccines among major developed nations, it is possible that we will see the United Kingdom experience both the earliest and strongest cyclical recovery.

Regarding the impact of Brexit itself on UK growth, estimates of the long-run total drag on GDP of a Brexit that included a free trade agreement (FTA) have generally been in the 4%–5% region 3 . A significant portion of this estimated impact however, perhaps up to half, has already occurred. This was via the generalised growth slowdown caused by heightened policy uncertainty. One of the primary manifestations of this was in the anaemic levels of business investment in the United Kingdom in the years after the referendum (Figure 2). As a result, between second quarter 2016 and fourth quarter 2019, UK GDP grew by 1.7% less than in the stereotypically low-growth Euro Area in real terms. It is possible that a portion of the drag from business investment is recouped, as pent-up demand for such investment is released by the newfound certainty.

FIGURE 2 BUSINESS INVESTMENT FLATLINED IN THE UK AFTER THE REFERENDUM

First Quarter 2006 – Third Quarter 2020 • Second Quarter 2016 = 100

Sources: Oxford Economics and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Looking forward, the non-tariff barriers the United Kingdom is now faced with when trading goods with the EU will have an impact on UK growth this year given their weight in total exports (Figure 3). The Bank of England (BOE) has estimated these costs will subtract 1% from first quarter 2021 growth. In the short to medium term, regulatory change in the services sector will also likely be a drag on growth, although the magnitude is harder to predict. More speculative still are the appraisals of the impact to long-run growth as a result of the new relationship. On the negative side of the ledger, the cumulative impact of a drop in investment, in addition to a potential reduction in immigration, may decrease productivity and therefore potential growth. However, there are some offsets to this. New trade deals that are in the works, including ones with the United States and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, should be somewhat additive to growth. Some benefit should also be derived from the scope to be able to set their own regulatory agenda in many industries. Such regulatory divergence, while valuable, will likely be limited by level playing field commitments. In the current environment, the importance of these future impacts from Brexit is diminished by comparison to the effects of the COVID-19–induced economic landscape.

FIGURE 3 THE EURO AREA REMAINS THE DOMINANT DESTINATION FOR UK EXPORTS

2020 • Percent (%)

Sources: Office for National Statistics and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: China data includes the mainland, Hong Kong, and Macao. Data are through June 30.

The EU will, of course, also be affected by the diminution of the trading relationship between the United Kingdom and itself. The relative size of the two economies however, implies that the economic impact on the EU will be more muted in the aggregate. The United Kingdom’s closest neighbours will face the largest impact, led by Ireland, with Belgium, the Netherlands, and France also hit. As is the case with the United Kingdom, the post–COVID-19 landscape will be more impactful on the economic outlook. The Euro Area is projected to grow by 4.3% and 4.0% in 2021 and 2022, according to median Bloomberg estimates.

Prospects Brightening for UK Assets

UK equities have been a particularly unloved corner of the market in recent years. Since the start of 2016, the cumulative return of UK equities has lagged that of broader developed markets by 67.2% in GBP terms. The reasons for this transcend just Brexit. The UK index tends to be tilted toward value, due especially to a large underweight to the IT sector. Naturally, this has been a drag on performance as growth has outperformed value and the IT sector specifically has exhibited such strong returns. In addition, the underperformance during 2020 was exacerbated by the outsized toll that COVID-19 took both on the UK economy and the energy sector in particular. This included sharply reduced dividend payouts, led by financials, as elevated dividends have traditionally been one of the largest attractions to UK equities.

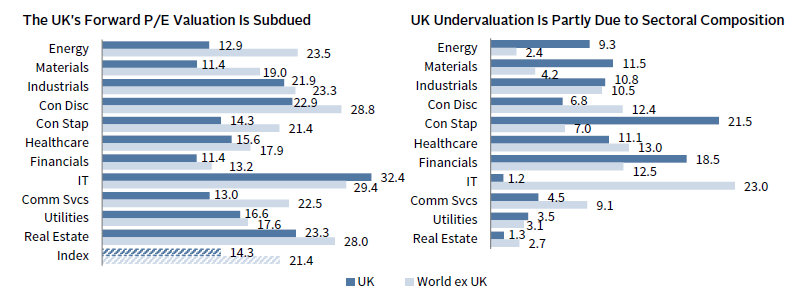

Cumulatively, these factors have made UK equities appear cheaply valued relative to other major developed markets. A large part of this is due to the composition of the index, with the MSCI UK Index having underweights to the most richly valued sectors (Figure 4). Looking at relative valuations on a sector-by-sector basis however, we can see that this undervaluation extends beyond just composition. Nearly all sectors in the United Kingdom trade more cheaply than their peers. Ironically, the IT sector is the one exception. The resolution of the Brexit negotiations may serve as a catalyst to reverse some of the discrepancy in valuation. Global managers that spurned UK equities due to the binary tail risk of a hard Brexit may now view the market as investable again.

FIGURE 4 UK EQUITIES TRADE CHEAPLY RELATIVE TO PEERS

As at December 31, 2020

Sources: Factset Research Systems, MSCI Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Data for UK are represented by the MSCI United Kingdom Index. Data for World ex UK are represented by the MSCI World ex UK Index.

Some of the non-Brexit factors that have weighed on performance may also turn into tailwinds as the economy recovers in 2021. Value stocks tend to be overrepresented in those cyclical sectors that have so far lagged since the onset of the pandemic, particularly financials. The direct effects of COVID-19 and associated lockdowns have impacted these sectors more forcefully, particularly in the United Kingdom, which is in the midst of its third national lockdown. Such cyclical sectors stand set to perform more strongly once economic activity starts to normalise. The current reflationary 4 backdrop looks likely to persist in the short term at least, which is supportive of financials and energy. The associated rise in yields may also begin to weigh on the sizeable valuation premium enjoyed by growth stocks. Finally, the expiry of a regulatory prohibition on dividends in certain sectors, alongside the recovery in energy prices, should see payouts increase in the United Kingdom in the coming months. In an ultra-low yield world, this should serve as an attraction for a broad church of investors, not just the income-hungry UK variety.

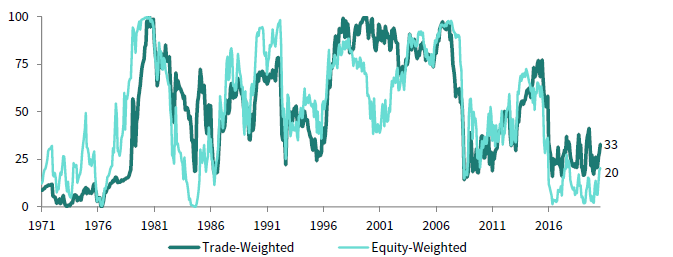

Elsewhere, the value of sterling on a real effective exchange rate basis remains subdued (Figure 5). To the extent that the newfound investable status of UK assets attracts capital inflows, there remains room for further appreciation of the currency. This is particularly true against the US dollar, which we believe has further downside ahead. 5 Finally, to monetary policy. While acknowledging that the outlook remains ‘unusually uncertain’, the agreement of an FTA with the EU removes one source of that uncertainty for the BOE, albeit the largest one still remains in the form of COVID-19. Recent comments from the governor and deputy governor do not indicate any pressing need to deliver further easing at this time. As such, we may have already seen the low in UK gilt yields. With the global reflationary theme still in play for the foreseeable future, a steepening of the UK yield curve looks to be the most likely outcome.

FIGURE 5 REAL EXCHANGE RATES SHOW THE GBP HAS ROOM FOR FURTHER APPRECIATION

30 June 1971 – 31 January 2021 • Percentile (%)

Sources: Eurostat, MSCI Inc., OECD and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Summary

Brexit dominated the economic discourse in the United Kingdom for more than four years prior to the arrival of COVID-19. The resultant uncertainty created headwinds both for the UK economy and UK assets. Now, the signing of the EU-UK TCA provides much needed clarity for many businesses, even if the immediate shape of the economic landscape will primarily be determined by the response to the virus. UK equities stand well placed to benefit from the cyclical rotation that could result from a normalisation of economic activity. Meanwhile, depressed valuations in equities and the pound sterling demonstrate just how out of favour UK assets have been. The removal of Brexit tail-risks should see renewed interest in UK assets from foreign investors, enticed by elevated risk premia. In combination with elevated valuations in the United States, we think the brighter UK prospects will support global ex US equities versus those in the United States.

Index Disclosures

MSCI United Kingdom Index

The MSCI United Kingdom Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the UK market. Launched on 31 March 1986, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float–adjusted market capitalisation in the United Kingdom.

MSCI World ex UK Index

The MSCI World ex UK Index captures large- and mid-cap representation across 22 of 23 developed markets countries (excluding the UK): Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. Launched on 31 March 1986, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float–adjusted market capitalisation in each country.

Footnotes

- Since June 2020, we have recommended investors hold a basket of small overweights to Asia ex Japan, global ex US, small-cap, and value equities. For more information on this topic, please see ‘Tactical CA House Views’, Cambridge Associates LLC, 2021.[/ref}

A Slim-Line Trade Agreement

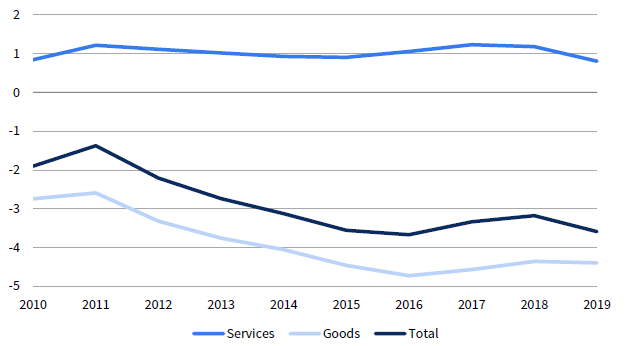

Importantly, this deal sees the parties end these negotiations on relatively amicable terms, even if the typical slings and arrows of a major trade negotiation at times gave the impression that this was not the case. It can serve as the foundation for future cooperation and perhaps even a gradual (re)coalescing in a number of fields. Given that both parties were coming from a position of extensive prior economic harmonisation, the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) represents a relatively narrow compact by comparison. The agreement focuses on the trade of goods, in which the EU enjoys a surplus, and is light in its coverage of services (Figure 1). Regarding its coverage of the trade of goods, the TCA provides for zero tariffs and quotas on all products. The deal on goods goes further than other free trade pacts the EU has signed, though a binding agreement on a number of issues remains absent. As of 1 January 2021, a customs and regulatory border now exists between the United Kingdom and the EU. This has already introduced friction on the movement of goods, even in the absence of tariffs and quotas.

FIGURE 1 THE UK’S TRADE BALANCE WITH THE EU SHOWS A SURPLUS IN SERVICES BUT A DEFICIT IN GOODS

2010–19 • Percent of GDP (%)Sources: Office for National Statistics and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

The subject of services makes the slenderness of the TCA apparent. There are provisions for limited visa-free travel between the blocs, which will help facilitate a continuation of certain services between the parties. However, the absence of pan-EU mutual recognition of professional qualifications will present a hurdle to UK service providers. The impacted firms will, for the time being, be required to either have their qualifications recognised in each EU member state they wish to do business in, or to establish a business entity within the EU itself. The lack of a framework governing trade in services is particularly evident in financial services. The sector was well prepared however, understanding that the loss of ‘passporting’[ref]The EU passporting system for banks and financial services companies enables firms that are authorised in any EU or European Economic Area state to trade freely in any other country with minimal additional authorisation.

- A ‘level playing field’ is a common set of rules and standards designed to prevent one country from undercutting their rivals in areas such as labour and environmental protection, state aid, etc.

- See, for instance, the Office for Budget Responsibility, ‘Economic and Fiscal Outlook’, November 2020, and Her Majesty’s Government, ‘EU Exit: Long-Term Economic Analysis’, November 2018.

- This refers to a phase of economic expansion, promoted by stimulative monetary and fiscal policy. It is characterised by rising inflation expectations, yield curve steepening, and often rising commodity prices, amongst other things.

- Please see ‘Outlook 2021: A Year of Healing’, Cambridge Associates LLC, 2020.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50+ years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients achieve their investment goals and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.