The Investment Portfolio’s Swiss Army Knife: Adding Private Credit to Portfolios for US Investors

In this paper, we investigate the uses of private credit. We start by looking at the return profile of different credit strategies. Next, we highlight three investor types (pensions, non-profits, and private investors) and assess the approaches each can take to incorporating investments in private credit. Ultimately, we view private credit as an underused and effective tool that can help a broad array of investors meet their objectives.

Defining Private Credit

Private credit has garnered a significant amount of attention in recent years, in part because of its remarkable growth. Assets in the space have gone from around $300 billion ten years ago to roughly $1 trillion today, according to Bloomberg. Much of this growth is in the United States, but European direct lending is on the rise, and so are growing opportunities in Asia. While many underlying substrategies of private credit pre-date the Global Financial Crisis, the crisis worked as an accelerant to private lending strategies, in particular, as banks exited business lines and limited their exposure to middle market lending for regulatory and consolidation reasons. This created an opening for private credit funds to fill an existing financing gap. Helping to drive supply of private credit funds were private equity firms that began adding private credit platforms as a way to take advantage of this vacuum in lending as well as to diversify their revenues. Meanwhile, demand came from some allocators looking to increase their target exposure to private credit, hoping to exchange some liquidity for incremental yield and often superior structuring.We define private credit as a fund that targets a high-yield or speculative-grade corporate, physical (excluding real estate), or financial asset risk in a private, lockup investment vehicle. Essentially, private credit uses the traditional private equity fund structure, oftentimes shortening its tenor and typically taking illiquid exposure to credit assets.

Private credit is not a monolith but rather consists of several different investment strategies. One feature that generally makes these compelling investments in a total portfolio versus, for example, equities, is the contractual return that exists in private credit. There is a legal promise of return of capital and, in most strategies, a promise of payment of interest or other contractual return. Whether a private debt strategy is built for income generation or for capital appreciation—as we shall see later—a contractual element to the private credit investment remains. Another related benefit to these strategies is that they can act as a risk mitigation tool relative to holdings in equities. Equity prices can fluctuate wildly, but a diverse set of debt investments can almost put a “floor” on returns in that portion of a portfolio.

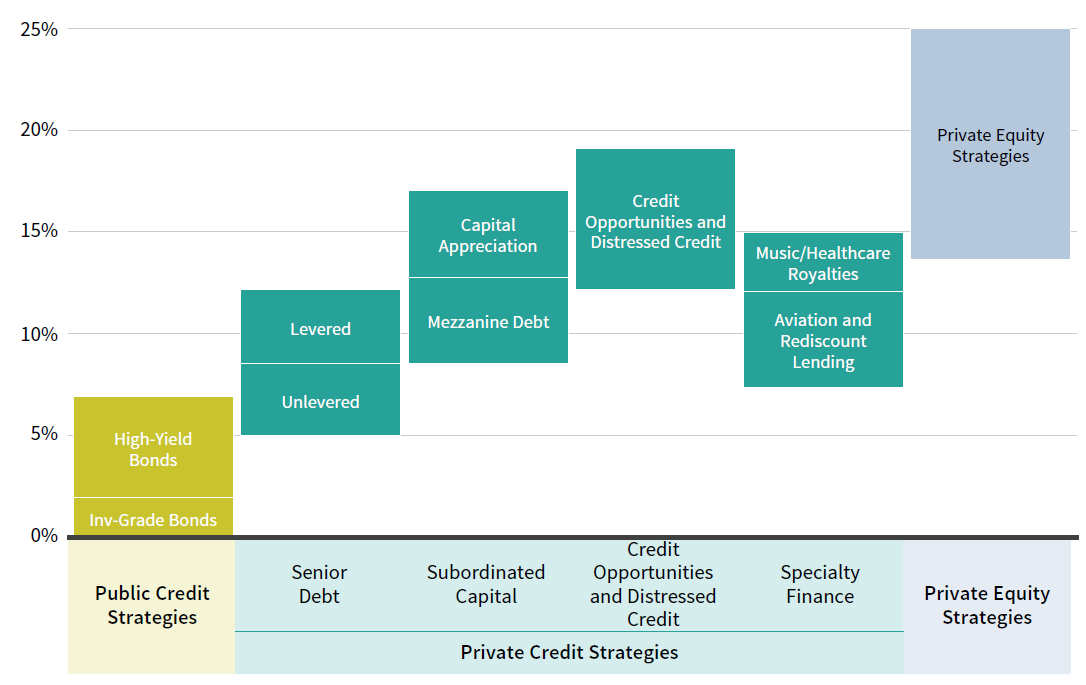

FIGURE 1 INVESTMENT-LEVEL UNDERWRITING TARGETS (NET IRR %)

As of June 1, 2021

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Note: Figures are intended to be directional.

Broadly, private credit substrategies can be classified into two categories: capital preservation and return maximization. Capital preservation strategies aim to generate predictable returns while reducing downside risk, i.e., preventing losses. These strategies include senior direct lending funds and mezzanine strategies (with mezz offering further upside from an equity component). Return maximization strategies focus on capital appreciation. These funds have the potential for greater gains than the “capital preservers,” but there is also greater potential for loss. Where most credit investments (e.g., bonds, loans) have a capped upside at par plus accrued interest, in the return maximization category, investments might be purchased at a discount that allows for price appreciation, similar to equities. However, downside risk between a portfolio of credits and a portfolio of equities is different. Indeed, downside protection is a core tenet of private credit (in addition to contractual return). Even in extreme scenarios (among return-seeking strategies like distressed, NPLs, insolvency, trade claims), the minimum level of return an investor will achieve is typically not that far below invested capital.

A third category that does not necessarily fit neatly among the capital preservers and return maximizers is opportunistic or niche specialty finance strategies. These types of funds should be evaluated individually to determine their potential return prospects. Some strategies might reside in the capital preservation camp, while others might best be classified as return maximizing strategies. Regardless of the magnitude of potential returns, the unifying factor among these specialty finance funds is that they tend to exhibit a diversifying return stream relative to other private credit. That is because of the idiosyncratic nature of the underlying assets in these funds, whether they be aircraft or healthcare royalties. These investments are often asset backed, and a significant portion of their returns comes from execution risk rather than credit risk. Their returns are driven less by corporate credit risk than other private credit strategies may be.

Three Investor Types

Different investors should use private credit differently. We look at the goals of three investor types, the role private credit can play in their portfolios, and the types of substrategies that tend to make their way into such portfolios.

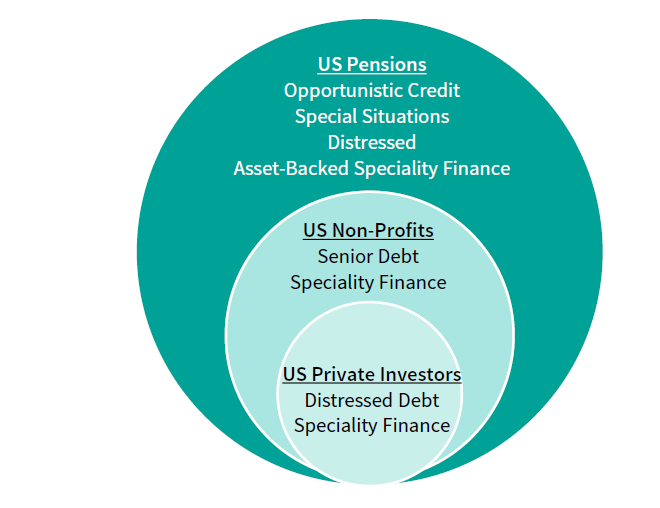

US Pensions

Pensions have been the largest allocators to private credit by dollars invested. In a Preqin report on the top 100 institutional investors in private debt by size of investment, pensions constitute 52% of the total. About two-thirds of the pension group is made up of public pensions, while the balance is from private pensions. And the amount of capital coming from pensions in the private credit space continues to grow. Public pensions added $34.7 billion in capital to private credit funds in 2020, up from 2019 and 2018. The average allocation to private credit by US public pensions is 3%, and Cambridge Associates advocates for an increased allocation among many of our clients. We work with a number of pensions that only recently approved a private credit allocation. Indeed, we partner with other pensions that remain underallocated relative to their private credit targets. As such we are actively working to deploy capital to private credit investments in these situations.

Pension portfolios may have a dedicated bucket for private credit investing, and along with that they will often build the dedicated portfolio around a return target. Pension investors should begin with defining the goal of the private credit allocation, which will help establish the orientation of that portfolio. For example, if the goal is to provide incremental yield relative to publicly traded liquid fixed income, then the portfolio would be built around a particular subset of the private debt world. Is the goal to be opportunistic and meant to offer velocity of capital (i.e., to see capital come back quickly relative to other private credit strategies)? Is the goal of the private credit allocation to act as a broad diversifier avoiding any meaningful correlation to corporate credit risk? The answers to these questions—which any type of investor should ask—help dictate portfolio construction.

Given their large size relative to other investors, pensions are the investors most likely to build full portfolios of private credit investments made up of several strategy types. Pension investors may have investments of various tenors and seek diversification across vintage and across underlying asset types.

The goal of an alternative to fixed income might lead pension investors to capital preservation strategies such as senior secured direct lending that could generate perhaps mid-single digits to low double-digit returns. An investor that is substituting private credit for a fixed income allocation must be mindful of the illiquidity of private credit; one could compensate for less liquid private credit by having excess liquidity in other parts of the portfolio. Investors with a goal of superior returns should look to return maximization strategies like opportunistic credit, special situations, and distressed. These investments could bring returns of low to high teens and perhaps more in a market dislocation; they still provide contractual returns in a lower-return period as well as downside protection in declining markets. A goal of diversification for the private credit book should include more asset-backed, specialty finance strategies that are less correlated to corporate credit.

FIGURE 2 THE ROLE PRIVATE CREDIT PLAYS IS BASED ON INVESTOR TYPE

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

US Non-Profits

Private credit has been establishing a place for itself in the portfolios of non-profit investors where it is a small but growing part these organizations’ total portfolios. Indeed, 2019 was the first year that NACUBO-TIAA included private debt as a standalone category in its Asset Allocations for U.S. Higher Education Endowments and Affiliated Foundations annual study. (The dollar-weighted average of all institutions in the study was 1.2% allocation to private debt, while the equal-weighted average of all institutions was 3.0%.)

In an environment with low rates on fixed income and stretched valuations in equities, endowments and foundations in particular may have a need to park capital somewhere. That has led many non-profit allocators to invest in private credit.

Compared with pension investors, non-profit investors tend to be more opportunistic in their allocations to private credit as they often target a narrower scope of strategies within private credit relative to pensions. While some non-profit investor portfolios have a dedicated sleeve for investments in private credit, others do not and might allocate to private credit from a broader “private investments” bucket. For non-profit investors with annual spending objectives, the degree of flexibility offered by private debt funds can be attractive. A higher velocity of capital in shorter average life investment vehicles allows for a quicker return of capital to investors than, for example, a typical private equity fund might afford.

When allocating to private credit within a private investments book, non-profit investors should be careful not to directly compare private credit returns with private equity returns. While a private debt strategy might have some potential for “equity-like” upside, that higher octane return might be the result of equity kickers or leverage employed. Nevertheless, a private credit strategy will tend to have contractual qualities that allow for more “credit-like” risk on the downside. Non-profit investors can be opportunistic about targeting funds with low-teens percentage annualized returns and attractive multiples on invested capital, while keeping risk in check through downside protection. This can mean strategies such as (levered) senior debt or certain areas of specialty finance, among others.

US Private Investors

Similar to non-profits, private investors have been somewhat opportunistic in their approach to private credit. In this context, private investors are generally wealthy individuals and family offices. These investors—particularly those subject to US taxation—face the challenge of significant tax implications of some private credit investments. Private investors may not consider investments such as senior direct lending attractive because much of the return in that type of fund is expected to derive from interest income and could be taxed as ordinary income.

For tax purposes investment returns in a fund can be classified broadly as either capital gains or ordinary income. When an asset that was held for less than a year is sold, any gain on that sale is taxed as ordinary income. Thus, instead of seeking to originate loans at par and collect a coupon, a preferred strategy would be buying an asset on the secondary market and then selling it after one year at a higher price. A good example of a strategy with such a larger capital appreciation component would be distressed debt opportunities. However, investing in distressed debt can be episodic, and investors might wish to invest in a more flexible mandate than just trading in distressed securities. The targeted returns of an opportunistic strategy might be less than those targeted by distressed debt funds, but a flexible mandate allows for more opportunities to invest in case the environment is not ideal for distressed. Another preferable strategy for US private investors could be capital solutions or specialty finance investments as an alternative to diversifying hedge funds, with caution used regarding the tax implications related to interest income in spec fin funds.

It is important to remember that ordinary income has historically been taxed at a substantially higher tax rate than long-term capital gains. For this reason, the returns obtained in a private credit vehicle must be analyzed carefully to understand which tax rule will apply to an investor’s gains.

For non-taxable private investors, many of the criteria mentioned for both pensions and non-profits are relevant. These investors tend to use a mix of approaches, with some adopting dedicated exposure in their strategic asset allocation and others remaining opportunistic. For both approaches, the allocation is normally carved out of a combination of fixed income and hedge funds. The goal is to create some diversification and ideally less correlated returns with a risk profile that is more attractive particularly today than either traditional bonds or hedge funds.

Conclusion

Private credit investments do not fit neatly in a box. There are many types of strategies with a range of returns that can cater to the specific needs of different investors. As a group, private credit can be the Swiss Army knife of an investment portfolio. It is flexible enough to achieve a range of return goals for investors. Private credit is also centered on downside protection, contractual return, and providing opportunities for diversifying returns in a low-yield, high asset price environment.

Adam Perez, Senior Investment Director, Credit Investments

Adam Perez - Adam Perez is a Managing Director for the Credit Investment Group at Cambridge Associates.