New Taxes on Endowments and Foundations? Four Steps to Take Now

New tax provisions in legislation recently passed by the US House of Representatives (the House Bill) would impose millions of dollars of new costs on many colleges, universities, and private foundations, if enacted. We recommend four steps nonprofit organizations can consider right now, without being too hasty, to ensure they are well-prepared and responsive should the proposals become law:

- Understand what might be changing: Follow the new proposals, including how they may evolve or change as the legislative process progresses.

- Assess the trade-offs and difficult choices: Analyze how the organization would be affected by the new proposals—if at all—and the trade-offs that additional tax burden could introduce between current spending and the future role of the endowment.

- Know what you own (and what to do with it now): Update the tax cost basis of the organization’s investments and consider transactions, like potential sales of investments with significant built-in gain, that could be worth taking before any new tax proposals are effective.

- Plan ahead for tax-favorable strategies should the new rules be enacted: Consider potential changes in investment strategies and implementation that could mitigate additional tax costs from the new proposals.

To watch our recording from June 5 on “Excise Tax Hikes: Is Your Endowment Ready?” click here.

Step 1: Understand What Might Be Changing

The House Bill would significantly increase the rate schedules for two types of excise tax currently paid by certain colleges, universities, and private foundations. Since 1969, private non-operating foundations have paid an excise tax, currently 1.39%, on net investment income (which includes realized capital gains). Approximately 50 colleges and universities have paid a 1.4% excise tax on net investment income since 2018. A recent sample of private foundation tax filings showed payments that ranged from 0–19 basis points (bps) and averaged 7 bps of asset value; payments were not surprisingly correlated with total investment return. 1

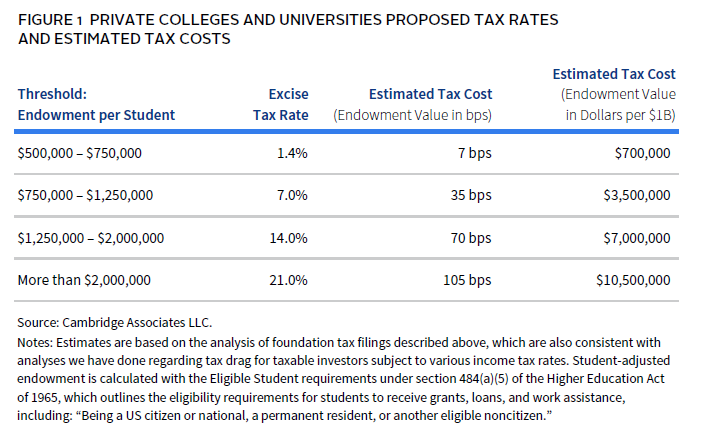

For private colleges and universities, the House Bill proposes new tiers of taxation that would significantly increase the applicable tax rates and potentially the number of colleges and universities subject to the excise tax. On its face, the tax would continue to be assessed only on private institutions with more than $500,000 endowment per student, but international students would be excluded from the denominator, increasing the endowment per student for almost all institutions. Figure 1 shows the proposed tax rates, as well as our estimates of tax cost.

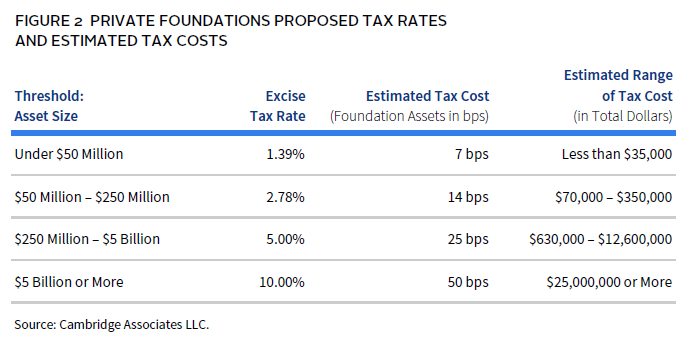

For most private foundations, the House Bill introduces new tiers of taxation based on asset size, as shown in Figure 2.

First and foremost, institutions should determine whether they would even be subject to the proposed new taxes. Most public charities, private operating foundations, and public colleges and universities would not be, unless they are sufficiently related to other institutions that are. Organizations potentially subject to the proposed new taxes should not be hasty in assuming they will be adopted exactly as set forth in the House Bill (or at all), since the road from House passage to enactment can be long and nonlinear, especially for major tax and budget legislation. Instead, the immediate focus should be on triage and preparation. We will continue to monitor the legislative process and update our perceptions and recommendations as needed, and affected organizations should do likewise.

Step 2: Assess the Trade-offs and Difficult Choices

Affected colleges and universities would be forced to make a difficult choice: either increase endowment spending and risk eroding the endowment’s purchasing power and reducing future institutional funding or pay the tax from operating funds, without increasing endowment spending. The latter effectively reduces available operating funds—whether viewed as a smaller endowment draw for operations or simply an added expense—creating immediate pressure to cut other costs or increase revenues, if possible. Colleges and universities do have other revenue sources in their financial equation, but they might have less flexibility to pivot to these sources if they are highly reliant on the endowment today. Endowment tax proposals are also coming at a time when university enterprises are additionally stressed by federal funding cuts and enrollment challenges.

Since this is an endowment tax, spending more from the endowment seems like a logical decision for colleges and universities to absorb the cost of the tax. Higher endowment spending also buys the operating budget some time to adapt. However, if the tax remains in place, it eventually reduces the value of the endowment. The costs of higher endowment spending today will be borne in future budgets, when a diminished endowment will yield less and less support. Institutions facing high costs of this tax will grapple with cutting costs sooner or later. Decisions will depend on the severity of the tax, current reliance on the endowment, and on flexibility to adjust expenses and raise other revenues.

Meanwhile, most private non-operating foundations are entirely reliant on the endowment to fund grants and program staff, so their choices are limited to reducing grantmaking to cover the tax (recognizing that the tax does reduce a foundation’s required distributable amount) or paying the tax in addition to established granting amounts, which may exceed sustainable levels (depending on the foundation’s investment returns and time horizon) and necessitate lower grant levels in the future.

In considering these choices, affected institutions should examine and model their current and anticipated spending needs, investment returns, budget flexibility, and revenue opportunities. This will enable them to assess the potential impacts of the new tax rules, consider steps they might take to mitigate those effects, and determine whether to absorb the tax as an additional expense or to offset it by reducing operating budgets or grant levels.

Step 3: Know What You Own (and What to Do With It Now)

Organizations that could be affected by the new tax proposals should update cost basis information for their investments to accurately assess built-in capital gain or loss. Unfortunately, it is not yet certain if the “correct” cost basis to use will be original acquisition cost or fair market value (FMV) as of a particular date, with potential modifications thereafter, so institutions might need to consider multiple possibilities.

- When the existing 1.4% college/university endowment tax was enacted in 2017, the statute was silent on this question, but subsequent IRS guidance clarified that FMV as of December 31, 2017, could be used as a starting point for investments acquired before then. Colleges and universities might reasonably assume that FMV date would still be relevant under the new tax tiers, or perhaps it will be December 31, 2025, right before the new tax tiers would take effect for these organizations.

- Private foundations could conservatively assume original acquisition cost (or December 31, 1969, FMV) will continue to be the relevant starting point for most assets, while hoping IRS guidance will allow FMV as of a date in 2025, at least for application of any higher tax rates above the current 1.39%.

- Whether the starting point for cost basis is acquisition cost, fair market value as of a specific date, or another measure, it serves only as an initial reference. Organizations will need to make appropriate adjustments to their tax basis. For example, with investments held in partnership form, cost basis can fluctuate as income, gains, and losses are reported out from year to year, even without distributions being taken.

For assets with significant unrealized capital gains to date under the worst cost basis assumptions, institutions should consider whether the asset should be sold to realize the built-in gain before the new rules take effect. These sales could be immediate, or they could be planned for immediate execution if the new rules are enacted, during the likely gap between enactment and applicable effective dates.

- These investment decisions will depend on several factors, including:

- The asset’s ongoing investment merits relative to others;

- The possibility of holding the asset indefinitely with little or no ongoing tax liability regardless of rates;

- The ability to reacquire the asset at a new, higher basis if desired (noting that “wash sale” rules, even if applicable, apply only to realization of losses, not gains), especially if the asset is generally unavailable for new investments; and

- Transaction and switching costs, manager constraints, and other logistical considerations.

Meanwhile, if they remain suitable investments, assets with unrealized losses to date may be worth retaining if those losses could later offset higher tax costs under the new rules.

Step 4: Plan Ahead for Tax-Favorable Strategies if the New Rules Are Enacted

If the new tax tiers are enacted, affected institutions should consider adopting some approaches that are already used by US taxable investors. These could include tax-managed direct indexing, as well as greater orientation toward investment strategies and entry vehicles with lower levels of ongoing income and gain and greater tax deferral benefits.

At the same time, institutions should also recognize that even the highest new tax rates will be far from the top individual tax rates, so some investment strategies (such as municipal bonds) will be less suitable than they are for taxable investors, and the costs and considerations described in Step 3 must still be assessed.

In addition to endowment spending and tax favorable investment strategies, organizations might also employ a range of other means to absorb the financial brunt of the new tax rules. For foundations, this may be a shift away from a perpetual time horizon or a contraction in grantmaking. For colleges and universities, these levers could include increasing enrollment to reduce endowment-per-student figures, directing new donations to current spending rather than to the endowment, and finding greater current funding from unaffiliated organizations. These other means will depend on an institution’s specific circumstances and must not run afoul of any anti-abuse authority or rules against circumventing the new tax provisions.

While the outcome of the tax proposals may evolve, taking practical steps now can help nonprofit organizations avoid last-minute decisions and better manage potential risks to the endowment. Careful preparation today may make it easier to adapt should these tax changes become law.

Footnotes

Tracy Filosa - Tracy is a Managing Director and Head of CA Institute.

Christopher Houston, J.D., CFA - Christopher Houston is the Head of Private Wealth Strategies in the Private Client Practice and a Partner at Cambridge Associates.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50+ years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients achieve their investment goals and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.