VantagePoint: What to Do About the US Dollar?

The US dollar and US equities have experienced a decade-long bull market that has significantly increased USD exposure across investor portfolios. Recently, the dollar has declined amid heightened global economic uncertainty, raising concerns about a possible prolonged downturn. Considering these developments, we believe investors should underweight the dollar relative to the allocation implied by their policy portfolio, or relative to the explicit target if one is stated. In this edition of VantagePoint, we examine the historical context of the dollar, outline why we believe the recent decline is likely part of a multi-year bear market, and discuss strategies investors can use to reduce their dollar exposure.

Understanding the Cycles: A Historical Perspective

Recent USD weakness has revived concerns about its “reserve currency” status. However, this erosion arguably began in 1971, when President Richard Nixon effectively ended the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system. Since then, the US share of global GDP and trade has declined from about 35% to 26%, while International Money Fund data show the USD share of global foreign exchange reserves peaked at 73% in 2001 and has since dropped to 58%.

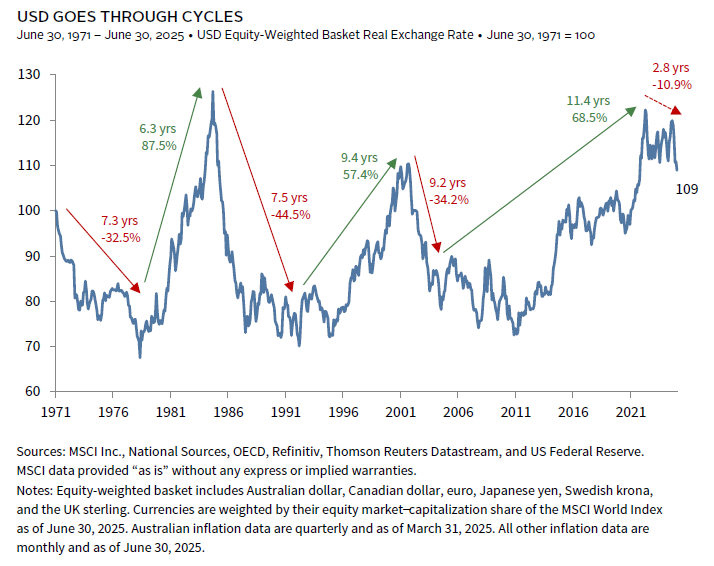

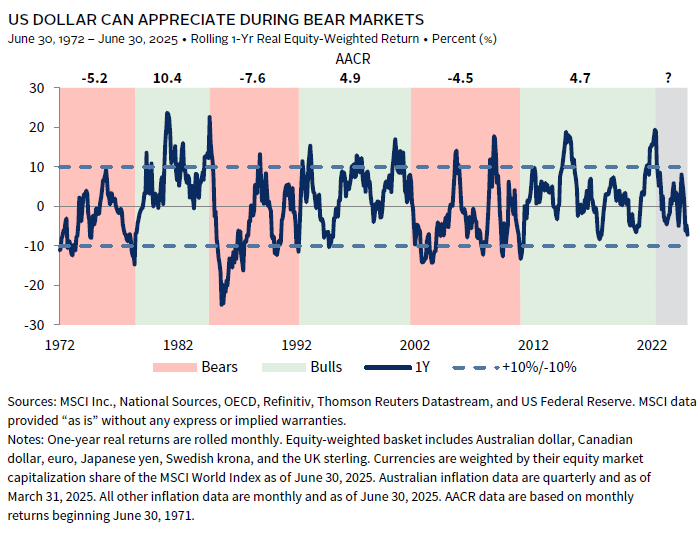

Concerns about the dollar’s reserve status resurface every decade. Since 1971, the US dollar has experienced three major cycles, with bull and bear phases typically lasting around a decade. With the US dollar peaking in late 2022 in both nominal and real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms, we are likely entering another multi-year bear market for the dollar, even as it remains the world’s primary reserve currency. The size of the US economy and its financial markets will likely sustain the dollar’s preeminence, but this does not rule out a significant extended cyclical decline.

Why Might the Cycle Be Turning?

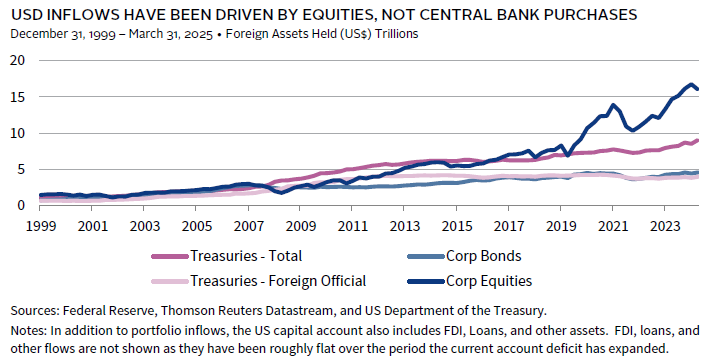

Portfolio inflows into US equities and bonds—not central bank reserve accumulation—have driven the dollar higher in recent years. These inflows surged due to higher US yields and the outperformance of US equities and the broader economy. This created a virtuous cycle: rising asset prices attracted increasing inflows—particularly unhedged investments—as investors sought to capitalize on a strengthening dollar and minimize hedging costs.

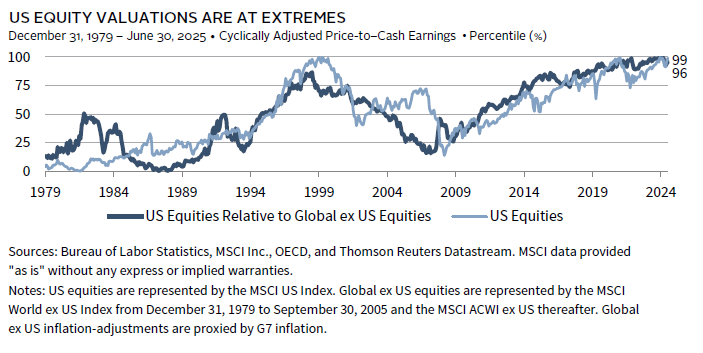

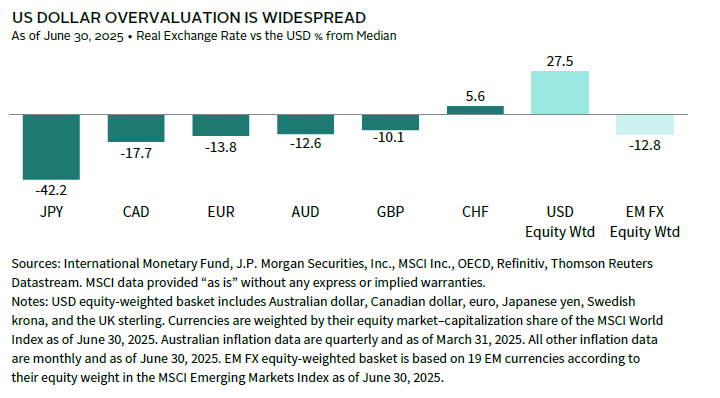

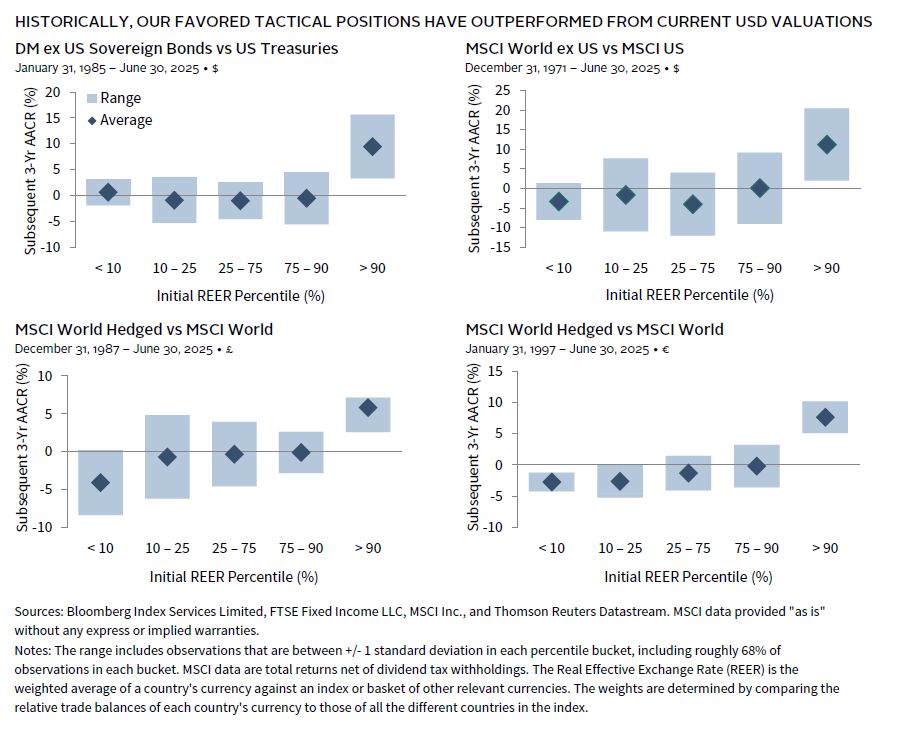

This cycle now appears to be reversing. US assets are markedly overvalued. At its recent peak, the real value of the dollar reached levels not seen since 1985, exceeding prior peaks in 1971 and 2002. US equities are also trading at extreme valuations—both in absolute terms and relative to global peers—and have started to underperform non-US equities.

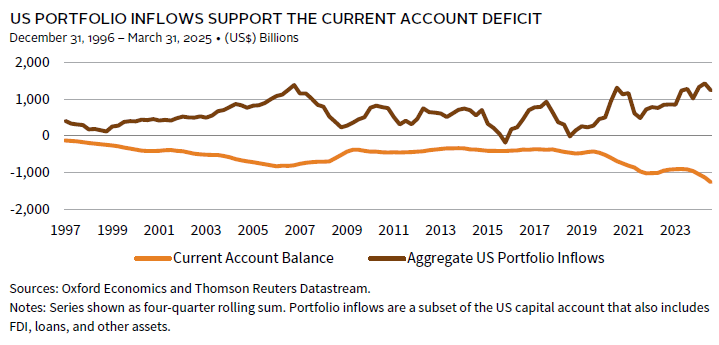

At the same time, ballooning US current account and fiscal deficits have increased US dependence on international capital. Portfolio inflows of approximately $1.2 trillion support the $1.3 trillion current account deficit, while foreign buyers make up 34% of the US Treasury market. For the dollar to remain strong, the United States must continue to attract enough capital to finance its deficits. If not, the dollar will fall, forcing deficit adjustments. Foreign investors do not need to sell their existing US assets for the dollar to fall; they simply need to allocate less. While the Trump administration has expressed a desire for more inbound investment, it is unclear if current policies will be effective. Furthermore, US tariff policies aimed at shrinking the trade deficit may reduce the supply of surplus dollars available for recycling into US assets. President Donald Trump has also advocated for a weaker dollar to boost exports and reduce the trade deficit. Talk of a “Mar-a-Lago Accord” to coordinate a USD devaluation has spooked foreign investors. In general, uncertainty over US economic policy may continue to prompt foreign investors to shift portfolios away from the United States, putting further downward pressure on the dollar.

US fiscal policy is also contributing to this reversal. Increased Treasury issuance and concerns over the sustainability of US debt levels have seen investors demand an extra risk premium to hold US Treasury bonds. 1 While higher yields have historically supported the dollar, this relationship has weakened as foreign investors now worry about both bond price declines and currency depreciation. A positive yield spread alone is not enough to support the dollar, and there have been periods in the past whereby the US dollar has weakened despite having a yield premium versus other currencies.

Fiscal and monetary divergence between the United States and other economies is another key factor. US trade and immigration policies are expected to both slow growth and keep inflation elevated. Consensus forecasts see US GDP growth averaging only 1.6% over the 2025–27 period versus the above-trend 2.7% rate seen over the past three years. Yet, despite slower growth, inflation is forecasted to average 2.7% versus the pre-pandemic average below 2%. With US government debt-to-GDP projected to reach 150% in the coming decades—driven in part by tax cuts from the recently enacted One Big Beautiful Bill Act—fiscal space in the United States will become increasingly limited. At the same time, the Federal Reserve may face constraints in lowering interest rates if inflation remains persistent. In contrast, the hit to growth outside of the United States is forecasted to be lower, while inflation is also expected to slow more. Thus, other countries may have more room to increase fiscal spending and lower interest rates, as recently seen in Europe and China. The result may be a cyclical boost for non-US economies, while curtailed US government spending and higher yields drag on US growth.

The US dollar’s resilience depends on sustained capital inflows, supported by superior growth, attractive asset returns, and stable fiscal dynamics. A productivity boom driven by artificial intelligence (AI), combined with large scale foreign direct investment related to AI infrastructure and reshoring/reindustrialization, could support the US dollar and limit future weakness. It remains to be seen to what extent the US lead in AI will be maintained and policies related to attracting foreign direct investment will be successful. Further, much of this AI optimism is already priced into US equities.

In sum, overvalued assets, policy uncertainty, and a deteriorating cyclical relative growth outlook are prompting capital to move away from the United States. This shift could turn the past decade’s virtuous cycle into a more challenging environment for the dollar, at least until valuations and deficits correct. Historically, periods of dollar weakness have seen declines of more than 30%. With the dollar down ~10% from its recent peak and still about 20%+ overvalued in real terms, there is ample room for further depreciation, especially since we are, at best, three years into what could be a ten-year cycle.

Is USD Weakness Already Priced In?

Bearish sentiment on the US dollar is quickly becoming consensus. With the US dollar down 9% year-to-date and 6% over the past 12 months, it is reasonable to ask whether the sell-off is overdone. Historically, it typically needs to fall more than 10% year-over-year before staging a meaningful rally. We may be approaching that threshold, suggesting a rebound could be on the horizon. USD rallies often occur amid market “risk-off” periods, consistent with the “Dollar-Smile” concept that states the US dollar tends to appreciate when US growth is either much stronger than elsewhere (as in recent years) or when US growth is much weaker (such as during a recession), prompting a flight to safety. Such rallies can happen even within broader USD bear markets, as seen in 1974 and 2008, when the dollar’s “safe-haven” appeal was questioned.

We are negative on the US dollar on a multi-year horizon, while recognizing the decline will not be linear. For example, the dollar will likely rally amid a US recession or a global risk-off scenario. Ultimately, US policy changes will shape the path, magnitude, and duration of any down cycle. For now, the path of least resistance appears downward, and investors should adjust portfolios accordingly. Among major developed currencies, the US dollar is most overvalued relative to the yen, but it also remains expensive compared to other currencies. Given that US dollar overvaluation is widespread, we prefer a diversified approach to US dollar underweights rather than concentrating risk by targeting one or two of the most extreme currency pairs.

Understanding Allocation Drift

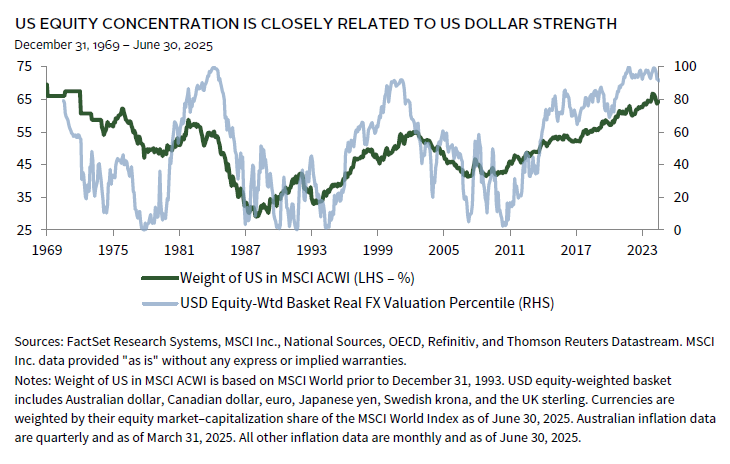

Many investors may not realize how much their USD exposure has increased as they have not actively increased allocations. The strength of the US dollar and US assets over the past decade has led USD assets to dominate market cap–weighted indexes, particularly in global equity benchmarks. At the end of December 2024, the United States made up 67% of the MSCI ACWI—the highest on record—up from 42% in 2010. This rise reflects both US equity outperformance and dollar strength, as index weights are based on USD market capitalization. If the dollar declines, the US equity weight in the MSCI ACWI will also fall, all else equal.

With the dollar about 20%+ overvalued, a decline of that magnitude could reduce the US weight in the MSCI ACWI from 64% to 52%. This would align with the 50% average US weight in the index since 1970. The MSCI ACWI weight to US equity will depend on both the US dollar and US equity valuations, but history suggests the current level may not be sustainable, especially if the dollar weakens.

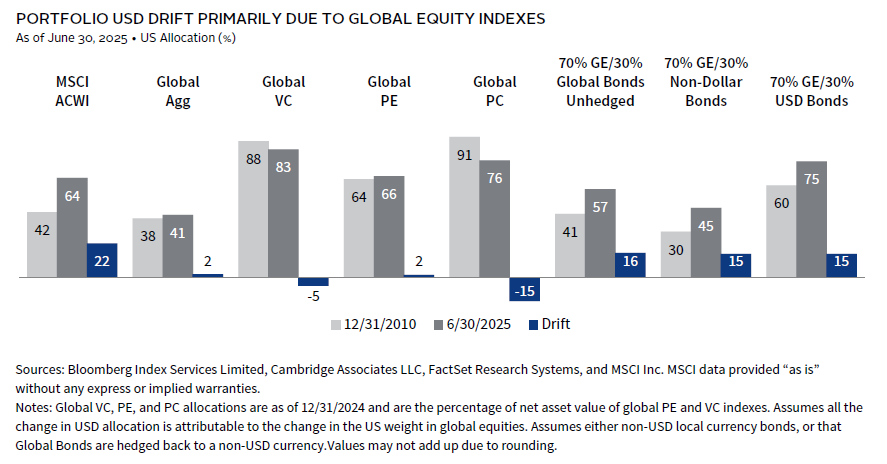

While the drift toward the US dollar in global equities has been significant, other asset classes, such as private equity and private credit, have seen more stable or declining USD exposure since 2010. Investor experience in private markets is likely to vary considerably as it is less common to have market cap–weighted allocations. Hedge fund portfolios are usually USD-dominated, but exposures can vary significantly across funds and over time, making broad generalizations difficult.

Experience across investors will differ, but in general, the primary driver of portfolio drift over the prior US dollar bull market will be due to the shift in global equity weights. In the simple example of a 70% global equity/30% bond portfolio, USD allocations have increased by about 15 percentage points (ppts) since 2010, assuming bond allocations are hedged to or denominated in the base currency. While the level of US dollar exposure differs for investors with USD and non-USD base currencies, the drift in a 70/30 portfolio is the same and driven by equities. This is because the total portfolio drift is simply the global public equity weight multiplied by the increase in USD weight within global equities (70% global equities multiplied by the 22 ppts increase in USD weight).

Diversified portfolios will have lower allocations to global equities, and thus are likely to have experienced less drift into US dollars and US dollar assets. For example, a portfolio with a global public equity allocation of 40%—roughly the median allocation of endowments and foundations—would have seen a USD drift of about 9 ppts, assuming its US equity share shifted similarly to the global equity index.

How Much US Dollar Exposure Is Appropriate?

There is no single “right” level of USD exposure, but a reasonable approach is to consider how much portfolio benchmarks have drifted because of US dollar strength. While the global public equity index has drifted 22 ppts toward the US dollar, we should not assume that will all be reversed in the coming cycle. A more conservative assumption would be a 10-ppt drop in USD share of global equities, bringing it close to what would be expected based on valuations and the historical average US equity/USD weight. Other considerations include asset/liability matching (i.e., the currencies in which investors spend) and tax implications of realizing gains on US assets.

Policy Change or Tactical Underweights?

For most investors, tactical positioning is the preferred approach to managing elevated USD exposure. We make this assessment based on our portfolio drift framework. Revisiting the example discussed above, an investor with a 40% allocation to global public equities would have seen total portfolio drift into USD assets of roughly 9% through the middle of 2025 since 2010. To get ahead of an expected unwind, we would tactically underweight the US dollar by 4 ppts, reflecting a 10-ppt decline in USD exposure for 40% of the portfolio.

While global equities have been the primary source of the USD drift, we do not recommend concentrating all moves away from the US dollar solely in global equities. Indeed a 4-ppt underweight to US public equities within global equities is a large portfolio bet that could overwhelm other sources of value added in the portfolio if it does not work out as planned. 2 Fortunately, there are other attractive means to tactically underweight the US dollar, such as underweighting USD bonds relative to non-dollar bonds or adding emerging markets local currency debt (EMD-LC) in place of USD–denominated diversifiers. Investors can combine several attractive positions in a risk-controlled manner to underweight USD exposures by 3 ppts–5 ppts.

However, in rare cases where portfolios have experienced significant drift into US dollars—particularly when the asset owner’s primary spending currency is not the US dollar and currency risk is therefore elevated—tactical adjustments alone may not be sufficient. In these situations, a more structural, policy-level change may be warranted. For example, in the case of an investor with a 70% global equities/30% bond portfolio that experienced 15 ppts of drift into US dollars, an underweight of 7 ppts would be required to address our expected 10-ppt unwind. Such large positions are better addressed through changes to policy portfolios.

When a policy change is appropriate, best practice is to secure buy-in from key stakeholders and codify the change in investment policy statements and benchmarks. This positioning should be reflected either through a currency policy (i.e., target currency exposure or hedge ratio) or a change in policy asset allocation targets, for example, by splitting the global equity benchmark into US and global ex US components. The strategy’s success should be measured over a longer horizon—typically five to ten years—by comparing the policy benchmark to a stock/bond volatility-equivalent benchmark. If valuations revert to historical averages more quickly, the policy underweight could be closed earlier.

Performance Impact of Large US Equity Underweights

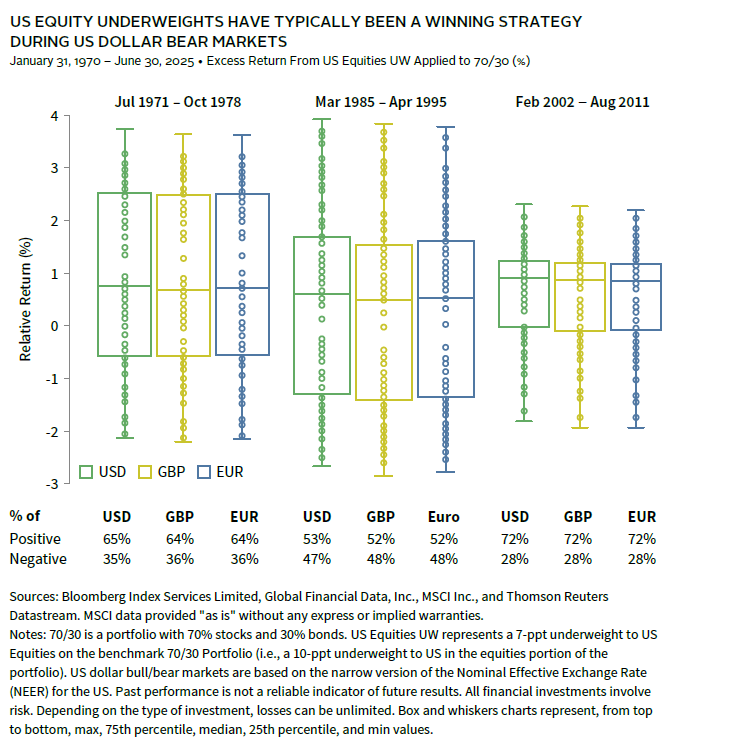

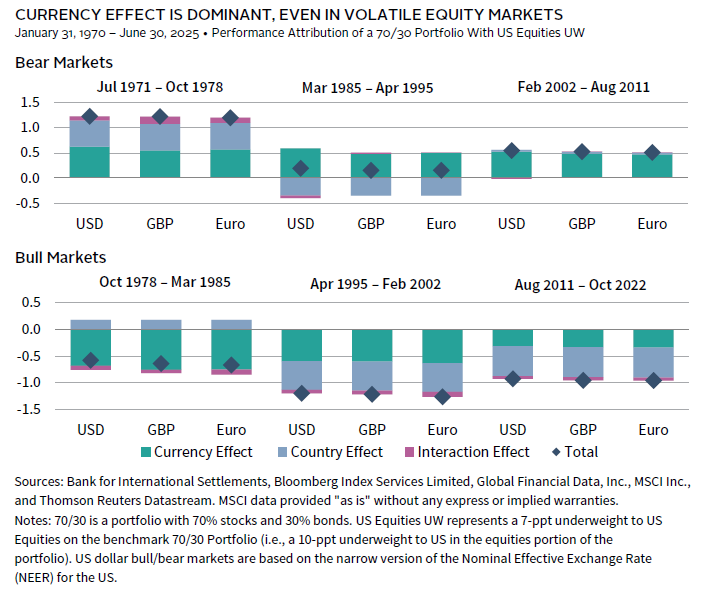

An investor with a 70/30 portfolio that underweighted the US dollar by 10 ppts during prior bear markets would have benefited over the full bear cycle but would have experienced frequent 12-month periods of underperformance, sometimes as significant as 2% to 3% at the total portfolio level.

Performance attribution analysis shows that most of the outperformance from such positioning during full USD bear markets came from the currency component, with the local currency US equity underweight playing a secondary—and at times, offsetting—role.

In summary, investors seeking to underweight the US dollar by more than 4 ppts to 5 ppts should reflect such positioning in investment policy.

What Should Investors Do?

For most investors, tactical positioning, such as overweighting non-US equities and unhedged non-USD bonds, is sufficient and appropriate. In cases where USD exposure in policy portfolios has drifted significantly higher, a policy change may be warranted, either through asset allocation shifts or increased foreign exchange (FX) hedging. Policy changes should be codified in policy benchmarks and evaluated over longer time horizons (5+ years).

Implications differ for USD-based and non-USD-based investors. Most USD-based investors have ample room to increase non-USD assets, whether by allocating to unhedged non-US equities or bonds, or by using global managers willing to tilt away from the United States. Increasing non-US private investments may also be warranted, but tilting public allocations to underweight US assets can help offset high USD exposure in private investments.

For non-USD-based investors, the situation is more nuanced. The upside to underweighting the US dollar depends on the degree of overvaluation relative to the investor’s base currency. Increasing hedge ratios or moving to hedged share classes may be more appropriate than overweighting non-USD assets, particularly for private investments and hedge funds. In general, hedging back to home currency—either via overlays or hedged share classes—should be considered for investors with sufficient scale to make hedging cost effective.

Reviewing the Menu of Options

There are several ways to reflect our negative view on the US dollar, including overweighting global ex US equities versus US equities, overweighting global ex US sovereign bonds relative to US Treasury bonds or implementing an FX futures overlay.

Increase Non-US Equity Exposure

The primary driver of increased USD exposure has been US equities, which are overvalued both in absolute terms and relative to global ex US equities. Since most unhedged FX exposure in portfolios comes from equities, increasing non-US equity allocations is the simplest way to reduce USD risk. This tilt typically results in less exposure to information technology and more to cyclical sectors, such as financials and industrials. Active global equity managers may already be making these adjustments.

Tilting private equity and venture capital allocations toward non-US assets will take time, but these allocations should also benefit in a multi-year weak dollar cycle. Still, currency considerations should not be the sole driver of private investment allocation decisions; manager selection and investment fundamentals remain paramount.

Increase Unhedged Non-Dollar Bond Exposure

Another appealing option is to increase unhedged non-US dollar bond exposure. Most investors hold domestic fixed income or hedge global exposure back to their home currency. Increasing unhedged fixed income exposure is relatively straightforward and provides more direct FX exposure than unhedged non-US equities, since FX volatility becomes the main driver of returns. However, overweighting non-USD or unhedged global bonds usually results in negative carry compared to US fixed income and increases bond allocation volatility. This trade-off—potential for extra return versus higher volatility—should be assessed carefully and may limit the amount of unhedged FX exposure appropriate for fixed income allocations.

Increase Diversifier Exposure

A more suitable place to take FX risk may be in “diversifier” allocations, such as absolute return fixed income or hedge funds (macro, trend following) that actively manage rates and currencies. These strategies offer indirect currency exposure, are actively managed, and provide less correlated sources of return. A more volatile and divergent macro environment should favor such strategies. EMD-LC is another asset class that should perform well in a weak dollar environment, offering attractive yields (6%+) and undervalued currencies with appreciation potential (10%+), along with diversification properties.

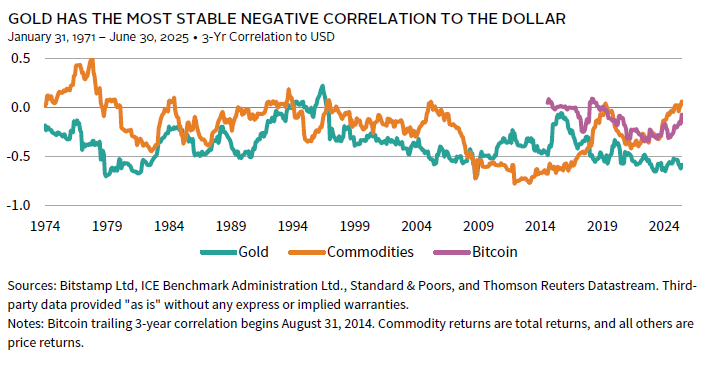

Commodities, Gold, and Crypto

Commodities and gold are traditionally seen as weak dollar plays, with prices typically rising as the dollar falls. Gold has the most consistent negative correlation to the US dollar, making it an effective—though volatile—way to play continued USD weakness. However, gold has rallied sharply in recent years amid geopolitical concerns and dollar weakness, which makes us cautious about recommending that investors chase it higher. Commodities are less reliable as a weak dollar play, as they remain vulnerable to slowing global growth and trade disruptions, and their correlations to the dollar have increased in recent years. Macro hedge funds may also provide exposure to these assets. Cryptocurrencies might seem like a logical hedge against dollar weakness, but their correlation with the dollar is unstable and the historical record is too limited for high conviction.

Currency Overlay

Another way to adjust currency exposures is through an FX futures overlay, either directly or via an overlay manager. This method does not require changes to underlying asset allocations or manager rosters and allows FX exposures to be quickly adjusted. However, overlays introduce operational complexity, costs, and the need to determine a specific hedge ratio. For instance, for USD-based investors seeking to reduce USD exposure, the overlay would go long on a specific currency or basket of currencies, thereby offsetting some of the portfolio’s US dollar risk. For this reason, reducing USD exposure through asset allocation changes is the most straightforward approach, particularly given compelling opportunities in non-USD investments.

Non-USD-based investors may find it more convenient to use home currency–hedged share classes, though not all managers/funds offer these. For example, private investments and hedge funds tend to be US-asset focused. Thus, non-US investors with large allocations to such strategies may have more USD exposure than desired and may need to consider overlay strategies to adjust overall portfolio USD exposure.

Conclusion

The US dollar’s decade-long strength has left many investor portfolios with elevated downside risk. For most investors, a tactical underweight to the US dollar is appropriate. The optimal level and method of USD reduction will depend on each investor’s base currency, portfolio structure, and risk tolerance. A diversified, risk-controlled approach—rather than concentrated bets—remains the best practice. By proactively managing USD exposure, investors can better position portfolios for a changing currency environment and mitigate the risks of a prolonged USD decline.

Drew Boyer, Grayson Kirk, and David Kautter also contributed to this publication.

Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index is a widely used benchmark for the investment-grade, USD-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market. It represents a broad spectrum of publicly traded bonds in the United States, including Treasuries, government agency bonds, corporate bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and asset-backed securities. The index is commonly used by investors to gauge the overall health of the US bond market and as a benchmark for bond funds.

FTSE® World Government Bond Index (WGBI) measures the performance of fixed-rate, local currency, investment-grade sovereign bonds. The WGBI is a widely used benchmark that currently includes sovereign debt from more than 20 countries, denominated in a variety of currencies, and has more than 30 years of history available. The WGBI provides a broad benchmark for the global sovereign fixed income market. Sub-indexes are available in any combination of currency, maturity, or rating.

The LBMA Gold Price benchmark is the global benchmark price for unallocated gold delivered in London, and is administered by ICE Benchmark Administration Limited.

The MSCI ACWI captures large- and mid-cap representation across 23 developed markets (DM) and 24 emerging markets (EM) countries. With 2,558 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the global investable equity opportunity set. DM countries include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. EM countries include Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index captures large- and mid-cap representation across 24 emerging markets countries. With 1,203 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float–adjusted market capitalization in each country.

The MSCI US Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the US market. With 626 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float-adjusted market capitalization in the United States.

The MSCI World Index represents a free float–adjusted, market capitalization–weighted index that is designed to measure the equity market performance of developed markets. It includes 23 DM country indexes.

The MSCI World ex US Index captures large- and mid-cap representation across 22 of 23 DM countries—excluding the United States. The index covers approximately 85% of the free float–adjusted market capitalization in each country.

The MSCI World 100% Hedged to USD Index represents a close estimation of the performance that can be achieved by hedging the currency exposures of its parent index, the MSCI World Index, to the USD, the “home” currency for the hedged index. The index is 100% hedged to the USD by selling each foreign currency forward at the one-month forward rate. The parent index is composed of large- and mid-cap stocks across 23 developed markets countries and its local performance is calculated in 13 different currencies, including the euro.

The S&P GSCI™ is the first major investable commodity index. It is one of the most widely recognized benchmarks that is broad-based and production weighted to represent the global commodity market beta. The index is designed to be investable by including the most liquid commodity futures, and provides diversification with low correlations to other asset classes.

The US Dollar Index measures the value of the US dollar relative to a basket of top six currencies: CAD, CHF, EUR, GBP, JPY, and SEK.

Footnotes

- We continue to believe that US Treasuries are a useful diversifier, while acknowledging the benefit of maintaining additional diversifying assets.

- We estimate that the tracking error of US equities versus global ex US equities is 11.5%, giving a 4.3-ppt position active risk of roughly 50 basis points, on the high side of our comfort level for tactical positions.

Aaron Costello, CFA - Aaron Costello is the Head of Asia and is responsible for the firm’s investment and research activities in the region.

Celia Dallas - Celia Dallas is the Chief Investment Strategist and a Partner at Cambridge Associates.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50+ years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients achieve their investment goals and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.