Private Direct Lending or Public BDCs? Guidance for Pension Plan Sponsors

Private credit has become a popular asset class among pension plan sponsors seeking yield enhancement over their public fixed income allocations. The non-bank finance market has flourished since the Global Financial Crisis due to a more restrictive bank regulatory environment, resulting in reduced bank lending activity, and a wide range of private credit opportunities are now available to plan sponsors. As these opportunities have expanded, private direct lending (DL) strategies have gained significant traction, providing a stable foundation to private credit programs. Plan sponsors can also access the private loan market through public business development companies (BDCs). BDCs have a comparable underlying strategy to private DL funds, but with important differences. Understanding the key characteristics of both can better enable plan sponsors to choose the strategy best suited to their portfolio.

Defining Private Direct Lending Funds and Public BDCs

Private DL funds invest in privately negotiated senior-to-subordinated debt issued by small and mid-sized companies. They offer attractive yields relative to traditional fixed income investments as well as lower volatility, especially for strategies focused on senior-secured debt. These funds typically have a five- to eight-year investment horizon, with a focus on generating stable income over time. Similar to DL funds, BDCs primarily invest in privately negotiated debt of small and mid-sized companies. They can also invest in distressed companies looking to restore their financial health. Unlike private DL funds, BDCs are public, closed-end investment vehicles that can be traded daily on an exchange.

Tracking the Juxtapositions

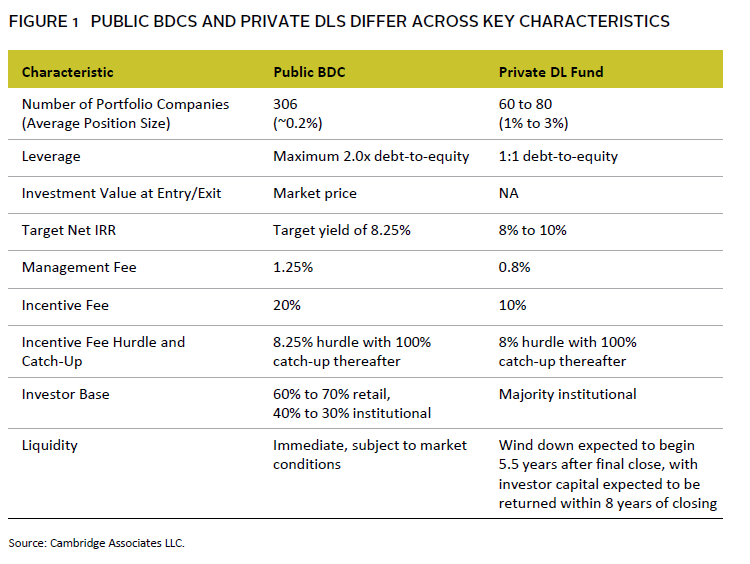

Public BDCs and private DL strategies differ in important ways, including liquidity and leverage, volatility, fees, underlying exposure, and loan origination opportunity. Plan sponsors should consider these differences carefully as they make determinations about their private debt exposure. Figure 1 depicts an example of a public BDC and a private DL fund offered by the same manager and how they differ across key characteristics.

Liquidity and Leverage

Private DL funds are structured as lock-up vehicles, with limited liquidity and redemption provisions for investors. However, the DL market has recently created more evergreen fund structures, which use a two- to three-year lock-up as the fund is invested, followed by the option to reinvest principal or have the position pay down over time as loans repay.

BDCs offer daily liquidity, which allows sophisticated investors to take a more short-term, opportunistic investment approach to these strategies. For example, BDC investors can trade in and out of funds as pricing fluctuates in response to economic conditions, fund-specific performance expectations, and market sentiment. A potential downside to this greater liquidity is the added risk of spikes in selling activity during heightened periods of market stress. This can create forced selling situations and a cycle of downward pressure on fund price and net asset value (NAV), especially if the BDC employs leverage in an effort to amplify returns. Public BDCs can be levered 2:1, with most hovering around 1.2x to 1.25x. This is an additional layer of risk that investors need to be comfortable with.

Volatility

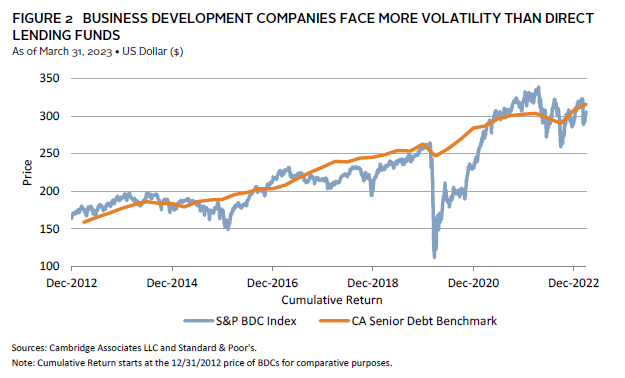

As shown in Figure 2, the realized volatility of BDCs is significantly higher than DL funds. Because they adjust their valuation marks on a quarterly basis—as opposed to daily pricing—the volatility of DL funds tends to be quite low. By contrast, the fact that BDCs are priced daily and can be traded opportunistically could result in greater volatility.

An additional factor that contributes to BDC volatility is the profile of the investor base. As a public, exchange-traded product, BDCs are predominantly owned by retail investors, which, in periods like March 2020, can result in sharp drawdowns in price from retail sentiment that is detached from the NAV of the underlying loans.

Fees

As a publicly traded, marketable alternative investment strategy, BDCs have historically mirrored hedge fund pricing, charging a 2% management fee and 20% incentive fee. While this has moderated over time, public BDCs are still priced at a premium, particularly when compared to private DL. In addition to the higher base fee, public BDCs have administrative expenses as ’40 Act funds that can push total expense ratios up more than 2% in some cases. 1 The relative stability and size of private DL limited partners reduce administrative costs for managers, which put downward pressure on base fees. On top of this, private DL funds typically have a lower incentive fee versus public BDCs.

Underlying Exposures

Private DL funds typically provide “pure play” exposure, offering investors privately negotiated senior debt issued by small and mid-sized companies, often underwritten to fairly consistent parameters and senior in the capital stack. BDCs, on the other hand, provide more varied exposure, with investments in both debt and equity securities. Even on the debt front, BDCs will often provide for a range of investments from senior to subordinated in the capital structure. BDCs are required to invest 70% of the portfolio into qualified assets with the remainder—up to 30%—in “non-qualifying” assets, which often take the form of subordinated debt, preferred equity, and/or common equity. As a result, the risk profile of the BDC portfolio is typically higher than that of a DL fund, with more exposure to junior capital as well as equity securities.

Newly Originated Loans Versus Existing Portfolio

When an investor commits to a new DL fund, the exposure to newly originated loans is built over time. On the other hand, when investing in a traded BDC, the investor is buying into an existing portfolio of loans and securities that were originated over the prior several years. While buying into an existing portfolio can mitigate the J-curve effect and reduce blind pool risk, the investor needs to be mindful of the credit quality of the underlying portfolio. 2 This distinction is more pronounced than ever, given recent increases in interest rates as well as improved loan structures and wider loan spreads on new originations, making the current entry point particularly attractive. Buying into a portfolio of loans that originated over the last several years—a time with more borrower-friendly terms and underwriting with significantly lower interest rates—could result in higher impairment ratios, which may explain why the pricing of the BDC is below NAV. Fundamentally, investors in BDCs need to understand the credit risk of the book of loans they are buying into when investing to avoid the potential for unexpected credit losses.

Finding the Right Fit

The current market environment—characterized by high interest rates and tight lending conditions—may be tailormade for private credit. Investors considering private debt strategies should evaluate the risk/return profile of the fund investment and whether it is going into a private credit program or an opportunistic, trading-oriented allocation. Direct lending may be a fit for plan sponsors looking for a steady, foundational investment to add to their longer-term designated private credit allocation. Those looking for a liquid, income-generating, opportunistic trading opportunity may want to consider BDCs. While both strategies can deliver benefits, pension plan sponsors should evaluate their risk tolerance, liquidity needs, and fit with their strategic asset allocation to determine the best approach for their portfolio.

Ian Monteith, Senior Investment Director, Pension Practice

Sheila Ryan, Managing Director, Pension Practice

Footnotes

- A ’40 Act fund is a pooled investment vehicle offered by a registered investment company, as defined by the Investment Company Act of 1940.

- A J-curve is an early period characterized by negative returns and cash flows, as investments are initially made and develop over time before they are in a position to be sold. “Blind pool risk” refers to when a limited partnership raises funds from investors without disclosing where the money will be invested.