Endowment Governance Part 3 – Process and Engagement

High-performing investment committees have a culture of doing the work, showing up (on time and in person), and making good use of time. A well-crafted agenda uses the committee’s opportunity to convene and covers topics that are conducive to discussion and propel decisions. Precious meeting time should not be used to reiterate information that can be read in advance of the meeting; meetings should be used to augment that information and promote discussion.

Disciplined work habits and clear expectations provide conditions for success and position members to meet their fiduciary responsibilities. With clear expectations that committee members will come to meetings ready to contribute while they are together, each member can have confidence that their effort will be valued and matched by colleagues. Talented people will want to join a group that they know is going to function well, do important work, and respect their time and abilities.

Investment Committee Meeting Details

Agenda. The agenda reflects the role of the committee and describes how the group uses its limited time together in person to oversee the endowment. The chair has a special obligation not only to attend meetings, but also to prepare for them in advance. Whether developed in conjunction with staff or an advisor (or both), the agenda is the chair’s particular responsibility. Effective chairs prepare and develop good agendas. In a good agenda, actionable items are prioritized, and enough time is allotted to give each suitable consideration. To accomplish this, the chair needs a clear idea of what outcomes they hope to achieve. This should not be confused with dictating decisions—a good chair dictates only the process of deliberation, not the decision itself, which should be that of the committee as a whole (or at least a majority).

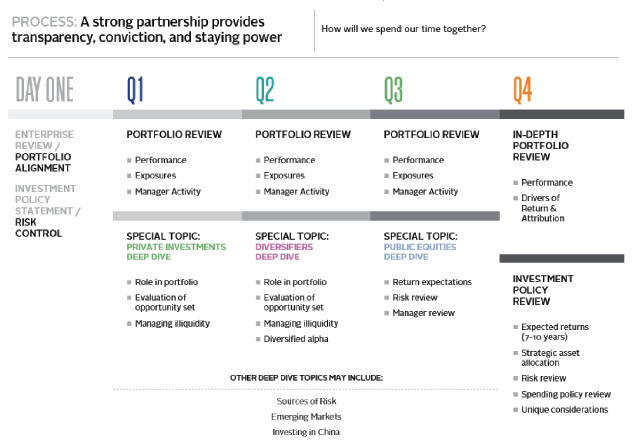

The chair also needs to keep the committee focused on business at hand. In other words, a discussion about the role of bonds in the portfolio should not be hijacked by a committee member who wants to recommend a particular hedge fund that a friend told him about yesterday. 1 Nothing is more common in committee deliberations than the tendency to meander down interesting but unproductive byways. The chair must exercise authority to prevent such digressions and must drive the discussions toward decisions (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 SAMPLE AGENDA

Frequency of Meetings. Best practice suggests that meetings be neither too frequent nor too infrequent. Given that the committee will evaluate performance, meeting frequency should reflect both the importance of oversight and the long-term nature of the endowment. Most investment committees meet quarterly, in conjunction with Board meetings, but should be prepared to meet more often during times of intensified activity. Quarterly meetings tend to strike the balance of keeping the committee sufficiently up-to-date but not burdened by meeting too often.

Meeting more often may make it difficult to attract many high-powered individuals whose professional calendars would rule out an overly active investment committee with too-frequent meetings. We have also found that committees who meet too frequently tend to spend time on more short-term events and let them drive decisions. Lastly, frequent meetings can have two possible unwanted and incongruous results: committees either feel compelled to make too many decisions to justify meeting, or they put off decisions because they can punt to an upcoming meeting.

Meeting Length. Regularly scheduled meetings should typically last two to four hours. Well-organized agendas with time allocations, strictly adhered to, allow investment committees to cover their responsibilities and to make the necessary decisions within this time frame. Probably the most common mistake among otherwise diligent and effective committees is the attempt to squeeze three hours’ worth of business into an hour and a half. Less common, but equally damaging, are loose, rambling meetings that drone on far too long, alienating those members who have better ways to spend their time. As British journalist Katharine Whitehorn eloquently summarizes: “Any committee that is the slightest use is composed of people who are too busy to want to sit on it for a second longer than they have to.”

Attendance. Investment committees should consist of members committed to attending all meetings. Best practice for investment committees requires that all voting members be present in person at every meeting. Occasionally a member may have to phone in for the meeting. But only in exceptional circumstances would a committee member miss a meeting altogether. Should this happen, there should be some standard mechanism for providing that member with a complete and thorough account of the deliberations. Usually the chair of the committee is expected to contact the absent member to inform him or her of what transpired at the missed meeting. It is inexcusable, and a waste of committee members’ time, for the absent member to show up at the next committee meeting requesting recapitulation of earlier discussions. 2

However, not all business requires a physical meeting and not all business requires the participation of the full committee. If regular committee meetings are held quarterly, for example, some business may be dispatched between such meetings by means of a conference call if there is simply too much on the plate to get through everything in just four sittings. Similarly, the chair may ask one or more committee members with particular expertise to oversee part of the portfolio (e.g., fixed income, hedge funds), serving, in effect, as the committee’s in-house expert on that topic.

A more elaborate form of this approach is the appointment of subcommittees, perhaps with qualified outsiders (e.g., alumni) asked to help with new or challenging considerations, such as mission-related investments, which demand considerable input, resources, and expertise. This can prove successful if carefully thought through, but beware! It may also have the unintended consequence of putting too many cooks in the kitchen, thereby compounding the inherent deficiencies of decision making by committee. The chair will need to determine any subcommittee assignments and the scope of their work.

Quorum. Best practice for Board committees is to have two-thirds of voting members constitute a quorum. As stated above, an investment committee should have all members present at any meeting, regardless of the stipulated quorum. This is because of the complexity, financial magnitude, and time-sensitivity of investment decisions, unlike (perhaps) the decisions of certain other kinds of Board committees.

Voting. Should the committee vote? Generally speaking, if—after discussion of each action item on the agenda—a vote can be called for as a matter of routine, then the record of (dis)agreement will be complete. Governance authorities favor this higher level of accountability. 3 Best practice requires that investment committee members vote on all major decisions. This would include changes in asset allocation, other strategic actions, changes in performance benchmarks, changes in risk parameters, evaluation and compensation of external and/or internal investment advisors or staff, and other governance matters. Votes should be explicit and recorded by name. An assumption that an action is approved unless someone “speaks up” denotes insufficient engagement and accountability. Voting does not need to be unanimous. In fact, an uneven vote may indicate committee deliberation and diverging opinions, all in support of the program goals.

Minutes. Best practice requires that all investment committee deliberations and actions be well documented. Both meetings and less formal conference calls should be recorded in minutes. 4 This includes at least the following: record of attendance; ratified minutes of each meeting; record of all votes, by name; record of recusals (if any) from discussions or votes; copy of each meeting agenda; copy of the discussion materials (e.g., research, analysis, data) used by the investment committee members to deliberate and discuss their decisions; record of timeliness of the receipt of such materials; and a copy of all reports received by committee members (such as performance reports). These should then be circulated to committee members as soon as possible both to solicit comments on their contents and to confirm the decisions made. And it is perhaps worth saying a word about the structure of minutes, since these are rarely a verbatim record of what was said, but rather a synopsis of the committee’s deliberations. As in any kind of memo directed to busy people, the most important items should come first, and in the case of investment committee meetings, the decisions are most important and should be highlighted at the beginning. In addition, a running chronology of committee decisions makes an excellent sidebar to meeting minutes.

Policies and Reports

An investment committee may adopt a number of policies. The required policies are an Investment Policy Statement (IPS), an endowment distribution policy, and a conflict of interest policy. Some investment committees also adopt a policy on gift terms, which govern the acceptance of capital donations to the endowment. In concert with the finance/budget committee, there may also be an operating liquidity policy and a debt policy (for institutions with public or private debt obligations).

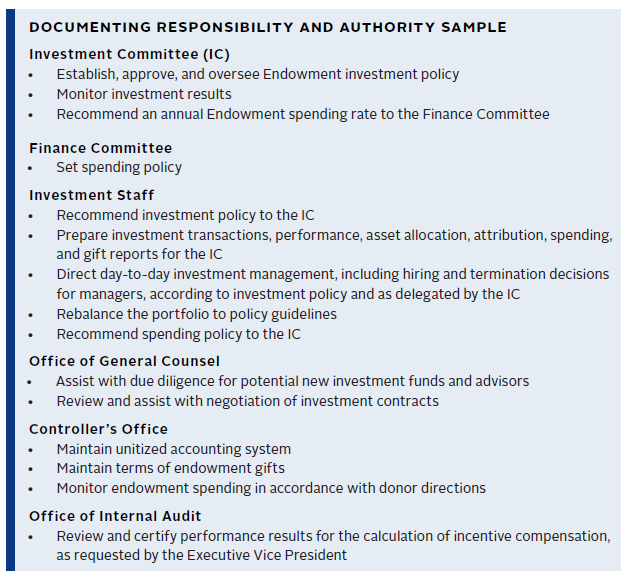

Investment Policy. The investment committee is responsible for setting investment policy. The IPS delineates the role and goals of the endowment (incorporating enterprise factors and constraints, if any), the portfolio return objectives and risk parameters, and strategic specifications such as asset allocation, performance benchmarks, and such other metrics as may be appropriate (e.g., liquidity, leverage, mission-related investing). The IPS may include investment roles and responsibilities and delineate specific tasks.

Policy statements sometimes indicate which tasks fall to which parties (again, governance/oversight tasks versus management tasks). The IPS should be reviewed every three to five years, or sooner if there have been institutional changes that impact the investment strategy, to ensure that it remains consistent with the committee’s strategic objectives and the institution’s circumstances.The IPS should specify the benchmarks for evaluating portfolio performance in terms of stated objectives, as well as asset class performance and other benchmarks, if any. Peer benchmarks may be cited but can be distracting when comparisons link institutions with different investment objectives and financial conditions. Peer context is one piece of information, but it should only be used as a benchmark when truly comparable. 5 Institutions should not rely on a “moving bogey.” Instead they should establish at least one meaningful long-term metric, and also include both financial and non-financial metrics (e.g., Do we have enough liquidity to meet spending requirements? Is the endowment keeping pace with institutional growth?).

Spending Policy. An Endowment Spending (Distribution) Policy may be a component of the IPS, or a standalone policy. Most endowments are guided by a “spending rule” that specifies the amount to be distributed from the endowment to operations each year. This may be determined by IRS regulations for foundations, or more flexible for universities and other operating organizations. In those cases, the spending policy is often developed in conjunction with the finance committee of the Board. Spending policy calibrates the balance between annual support of the mission and the long-term purchasing power of the endowment. There are several types of spending policies. The most common is a market value rule based on a moving average of the market value of the endowment over past years or quarters, multiplied by a percent spending rate. Some institutions use a spending rule based on the prior year’s endowment spending dollars; others use a hybrid of these two kinds of rules. The optimal spending policy should be linked to investment strategy, growth goals, and enterprise factors.

Meeting Materials/Reports. Meeting materials are key to a well-run and effective meeting, because they prepare and organize the group. Meeting materials should provide sufficient information to prepare members and avail additional details in an appendix or separate book if the committee members seek more background and diligence. Materials used during the meeting should be focused on the decisions at hand. Members should be expected to read materials in advance when they are engaging and focused on the right level of detail.

Meeting materials may vary by chair and the role of the committee. There is no single best practice or template for meeting materials and investment reporting. It is most important that materials respect members’ time and provide sufficient information for the committee to exercise their duty of care. Thoughtful investors find that effective materials are informative but also reasonable in what they are asking the members to consume in preparation. Materials should reflect the agenda and be organized to support their best work. Some committees work with very sparse materials that have been curated to stick to the essential information needed to make decisions when the group convenes. Other groups prefer “the phone book version” that provides highlights and supporting details. If the committee receives the unabridged version, it is important to clarify what is essential for the decisions on hand, and what is optional further reading. An appendix may serve this purpose.

The materials supporting committee discussion must be received by committee members at least a week before the date of the meeting, in order to permit time for members to read and evaluate the contents. Particularly for major strategic decisions at the portfolio level, time must be allowed for “homework” so that meeting discussions are productive and thorough.

Good Governance Is Stealth

Good governance can be so effective when it works smoothly in the background furthering institutional progress. Governance glitches or missteps, on the other hand, are headaches that can range from distracting to debilitating. No two institutions are exactly alike, nor are the people charged with governance responsibilities. Governance is not carved in stone, but the institutions that have achieved good governance have stability and continuity that are supported by fiduciaries with an investment committee mindset who are supported by excellent processes and work habits. They share a long-term orientation that reflects the pool of capital they steward. The people, process, and policies of these effective committees are led by leaders who value relationships and the role of the current group of fiduciaries in the long arc of the investment program. ■

Tracy Abedon Filosa, Head of CA Institute

READ THE ENDOWMENT GOVERNANCE SERIES

The “secret sauce” to long-term investment success is, in most cases, the governance that guides and oversees the investment program. Read part 1 of the series for details on the job description and part 2 to learn more about building the team.

Footnotes

- Indeed, there should be a standing policy of referring all manager suggestions from committee members, or others, to the staff or—in the absence of qualified staff—to an investment advisor for vetting, since this ensures these recommendations will be subject to uniform, objective evaluation criteria. It can also minimize unwarranted conflict of interest charges that can compromise the fiduciary duty of loyalty.

- Indeed, low participation may raise concerns about the committee’s fulfillment of the fiduciary duty of care.

- In most, if not all, US jurisdictions, the “business judgment rule” covers decisions with poor outcomes (“mistakes”) so long as there is demonstration of adequate fiduciary duty of care. Thus, going on record with votes should help, not hinder. Again, consult counsel for prevailing law on this matter.

- Institutions subject to public scrutiny might consider consulting their legal counsel on the question of how much detail to include in such minutes.

- Billy Prout and Grant Steele, “Finding the Proper Perspective for Peer Comparison,” Cambridge Associates LLC, November 2016.