Simplifying Family Investment Portfolios

For families of significant wealth, complexity is a natural byproduct of a well-managed portfolio. A dynamic portfolio can help address a number of investment challenges that families of wealth face, including varying multigenerational preferences, unique tax considerations, domicile requirements, and specific beneficiary needs. Yet there is also such a thing as overcomplexity, which can waste time, cause confusion, decrease potential returns, and increase risk. This paper reviews three indicators of an overly complex portfolio and discusses best practices for addressing them. Meeting multiple needs while protecting against overcomplication can help families maintain a prudent investment strategy and remain on track to accomplish their long-term investment objectives.

Indicators of Overcomplication

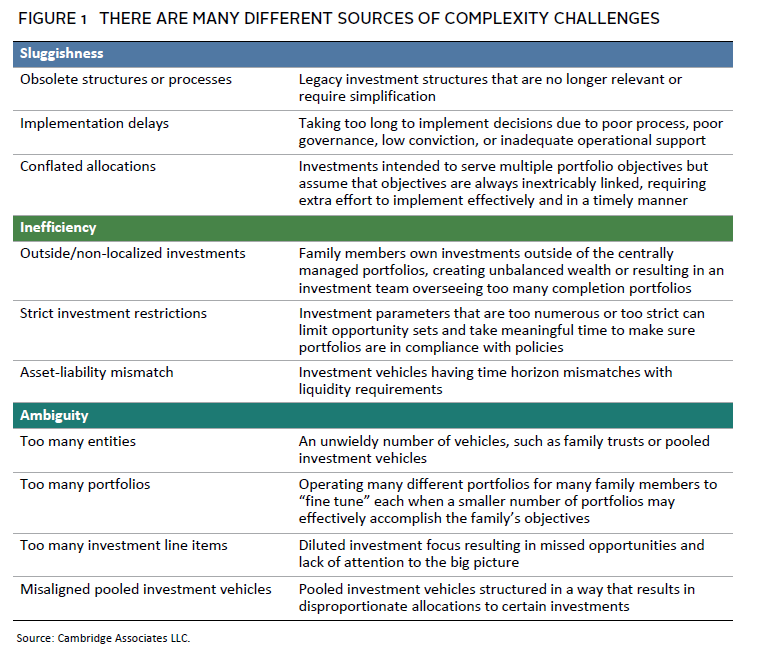

Portfolio management is hard work—it requires thoughtfulness and perseverance. That said, when a family’s portfolio operation routinely encounters sluggishness, inefficiency, or ambiguity, it may be a sign that that some simplification is in order (Figure 1).

Sluggishness

When an excessive amount of time is required of a family, its investment advisors, or its family office to manage a portfolio, it should be considered a warning sign. Invariably, if one or several aspects of portfolio management demand undue time and focus, less attention is paid to other areas, increasing the risk that something important gets missed. In some cases, additional staff and other resources can be helpful in addressing these challenges, but simply adding more moving parts often only serves to slow down already cumbersome processes.

Undue time demands and slow functionality can also result from administrative overload. A portfolio’s legal, regulatory, and reporting-oriented activities can consume inordinate amounts of time, especially as the volume of “know your customer” and anti-money laundering regulations has increased. When operational demands are unwieldly, it can inhibit the ability of investment practitioners to meet fiduciary obligations and optimize growth.

Inefficiency

A family’s investment governance and wealth management design can also create adverse complexity, leading sometimes to inefficient decision making and suboptimal deployment of capital. Disorganization and redundancy can occur in both governance and investment portfolio hierarchies. Delays in making investments caused by structural challenges—for example, unavailable cash in one entity and surplus cash in another—not only create extra work but prevent optimal deployment of capital. Awareness of these pain points is not enough—they should be actively addressed in service to the larger wealth management ecosystem. The amount of time required to effectively manage a portfolio will vary for every family. Ultimately, the best measurement is a family’s ability to make and act upon prudent investment decisions, which is critical to avoiding undue risk and to taking advantage of growth opportunities as they arise.

Ambiguity

The breadth and volume of information available to investors have increased significantly over the last decade, obscuring the best path forward in some cases. Filtering through the noise to determine what data and research are useful can be challenging and sometimes results in strategic and tactical ambiguity. This can lead to confusion and overcomplication in managing a family portfolio. For example, a single portfolio designed to account for family-wide differences in risk tolerance, time horizon, tax situations, and spending needs may be covering too broad a remit in theory and accomplishing very little in practice. For some families, too much complexity is manifested in excessive risk controls and benchmarks that are too granular. As a result, the investment team may be less motivated to take risk, potentially causing long-term performance to suffer. In other cases, some investments may be so small that their potential contribution to returns is minimal, while others may be so large that they have an outsized positive or negative impact on overall performance. Ensuring the portfolio is properly calibrated to the family’s overall investment objectives is key.

Three Steps Toward Simplification

The most successful portfolios are those that follow a deliberate, long-term investment strategy—one that is thoughtfully reflected in their design and construction. Therefore, prioritization of objectives is a key first step to countering overcomplexity and maximizing efficiency. From there, a clear view of the portfolio’s overall organization takes shape, allowing for customization preferences to follow.

Step 1: Prioritize

A family’s investment objectives and long-term financial goals should drive its entire wealth management engine. It is important not to spend too much time and energy focusing on past performance or practices. Instead, attention should be focused on managing future risk scenarios and determining how to best position the portfolio to succeed. Here, a clear understanding of performance expectations, risk tolerance, and short- and long-term requirements is essential to developing the best structure, governance, and investment philosophy for accomplishing the family’s goals. Oftentimes, the desire to clean things up comes from a generational transition. Steps such as restructuring a set of family investment vehicles to simplify decision making and operations and reducing the number of investment vehicles can help families refocus on what’s important. Families and their investment teams should remember that if everything is a top priority, nothing is a priority—and unwarranted complications can result.

Step 2: Organize

The design of a family’s wealth governance structure and investment hierarchy should directly correlate to its highest priority investment objectives. These designs can either be simple or varying and dynamic, irrespective of the number of principal wealth owners involved. Regardless of size and scope, organization is paramount.

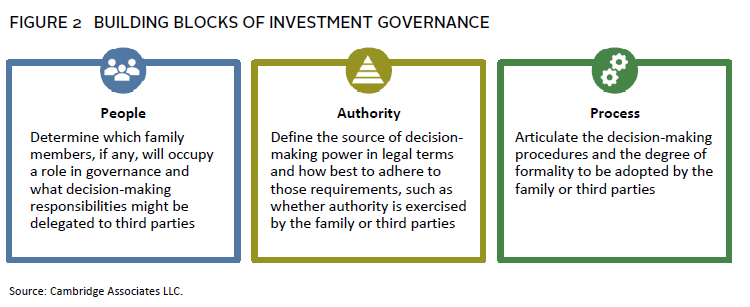

As they think about their wealth governance structure, family investors can build or realign their approach by considering three building blocks: people, authority, and process (Figure 2). “People” represents the stakeholders within the family and/or family investment team who participate in key decisions, with accordant models for both individual and multiple decision makers. “Authority” references the need to make clear determinations around the nature and source of investment management decision-making power. Similarly, this authority can be organized among a few or many stakeholders and shared among family members and third-party investment service providers. “Process” is about the degree of formality that wealth governance decision makers follow. A clear governance process will result in more effective investment management.

The governance structures best suited to families are those that align with their broader investment objectives without being cumbersome or excessively bureaucratic. The most effective governance models allow for thoughtful analysis of the risks and opportunities presented by the market environment and for the portfolio to be positioned accordingly.

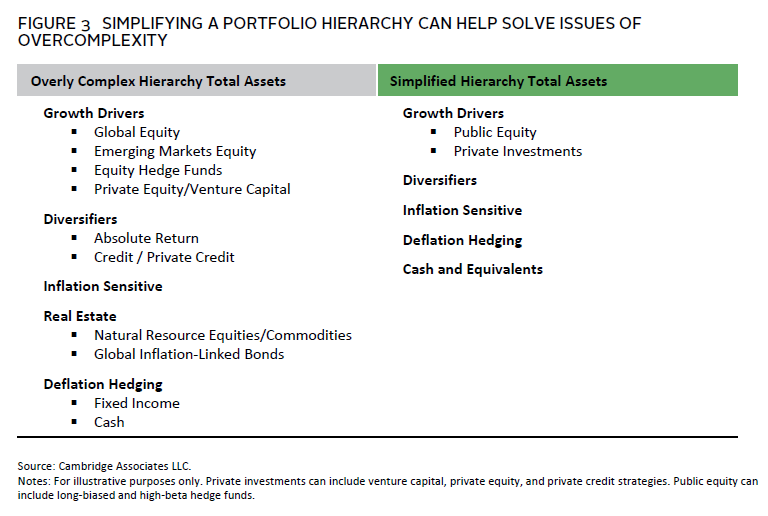

Beyond governance, a well-ordered investment portfolio hierarchy will also help families avoid becoming sidetracked by overcomplication. This hierarchy helps to set the parameters of investment management, including any allocation rules and asset class constraints stipulated by the family. Each investment should have a clear role in the portfolio. Investors should know exactly what each line item in their portfolio is seeking to achieve. Having this clarity can help investors solve issues of overdiversification.

Investors should also avoid portfolio hierarchies that attempt to be overly specific (Figure 3). Adding too many asset classes, sub-asset classes, and overly wide or narrow allocation ranges, as well as setting too many specific targets, increases the likelihood that such constraints will be violated. It also heightens the risk of suboptimal allocations.

Allocation parameters should correlate with the family’s established risk tolerance and liquidity needs. When establishing an investment hierarchy, considerations should also be made about the total number of investment managers in the portfolio, through either a prudent range of line items in each asset class or consideration of various risk measures, such as active risk.

Another common challenge for families of wealth is negotiating the balance between a concentrated and well-diversified portfolio. In many cases, concentrated positions can form unintentionally—for example, through inherited wealth or by holding stock in a family-owned business. Over time, some families can also demonstrate a predilection to invest in the industries that they understand the most, thus risking a lack of diversification. On the other hand, portfolios can evolve to become overdiversified through the constant addition of investment ideas and hesitation about culling the portfolio of line items that no longer serve their role or whose role is effectively captured by other, higher conviction investments.

Each end of the concentration/diversification spectrum has its risks:

- Too much concentration can wield too great an influence—both positive and negative—on the broader portfolio. Conversely, holding many disparate allocations can make the overall performance of the portfolio too difficult to monitor and maintain. Ideally, families should seek to make allocations that are large enough to have an impact, but not large enough to hurt the portfolio meaningfully should something perform differently than expected.

- On the other hand, portfolios are sometimes thrown together combining manager introductions from a family’s network, direct and co-investments, and a range of more esoteric investments (wine, cars, art, etc.). By adding more and more managers, the focus on important portfolio goals can be lost. Families can then become preoccupied with what is perceived as “not working”—at times even focusing on making significant and possibly unnecessary changes to investments playing an important role in the context of the overall portfolio. All of this can result in too many line items, which multiply over time when there is no effective oversight or desire to end a manage relationship. Fewer line items require more thoughtful portfolio construction and allow for an increased capacity to understand each investment’s purpose.

Step 3: Customize

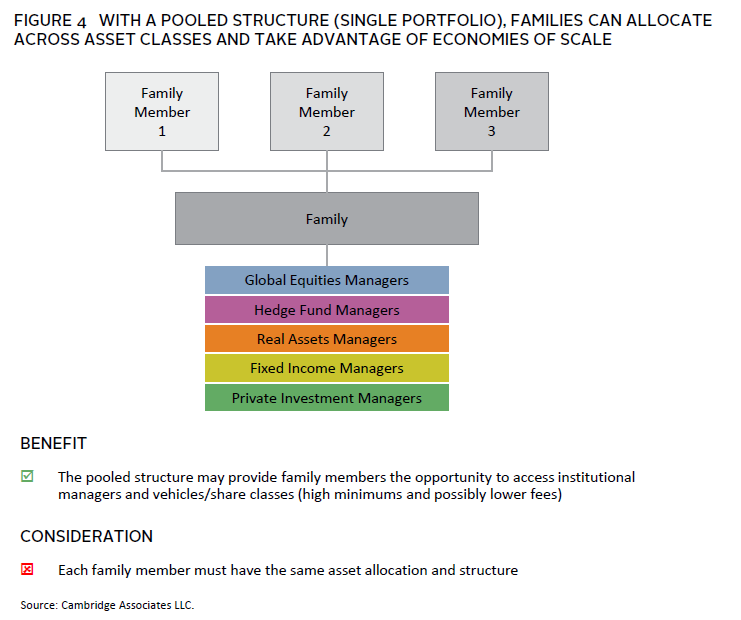

Clear priorities; well-organized, decision-making systems; and thoughtfully constructed investment structures allow for families to carefully customize their investment management as necessary. Some pooled investment structures, for example, enable cooperative capital allocation by family members across the portfolio, aggregating their assets in one or a handful of portfolios in order to take advantage of economies of scale (Figure 4). These include meeting minimum investment amounts, achieving fee break requirements, and simplifying administration and documentation processes.

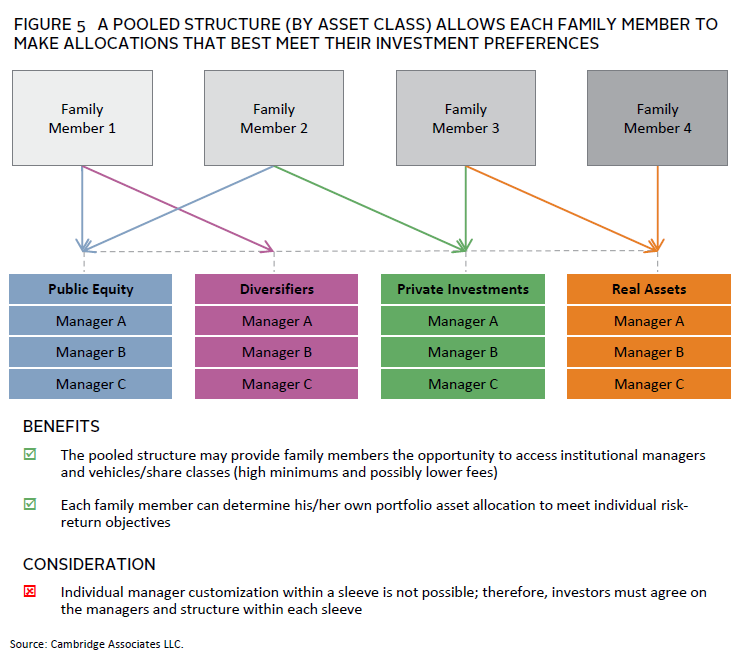

Families looking to meet a wider range of investment preferences and interests can use pooled structures that allow for family members to allocate across asset classes as pertains to their specific circumstances. Such families can establish a limited liability company—or equivalent vehicle based on domicile considerations—that is collectively owned by family members and focused solely on specific types of strategies, such as alternative investments. Pooled structures allow family members to make allocations that best meet their risk, return, and liquidity profiles. Many families combine both approaches, using both pooled individual and family-oriented portfolios, where preferred (Figure 5).

For larger family groups, the creation of additional portfolios designed to complement direct holdings and other outside investments can become a source of overcomplexity. Each of these portfolios might be radically different from one another, resulting in a vastly different set of objectives and allocations. Here again, establishing clarity around what allocations are meant to serve as a family growth engine and what allocations are meant to enhance diversification can help mitigate inefficiencies and wasted time.

Conclusion

Elegant investment solutions designed to meet the varied objectives and preferences of family investors can be fairly complex. In fact, dynamic solutions are often necessary. Determining the level of complexity required for a family’s investment and wealth governance approach requires experience, knowledge, and patience. No single formulation will be appropriate for all families. Yet overcomplication that results in sluggishness, inefficiency, and ambiguity will ultimately only increase risk—including the risk of underperforming goals and realizing permanent capital loss. A family’s investment priorities and wealth governance design need to be clear so that prudent customization can follow. Portfolios can be multifaceted, but their multidimensionality should help—not hinder—the work of serving a family’s investment objectives and long-term financial goals.